"JAPAN: RUNNING ON EMPTY," BY MICHAEL TOMSON (1979)

Michael Tomson covered the four-event 1979 Japan leg of the WCT for Surfing magazine. The article ran in the October issue. This version has been lightly edited.

* * *

It was Sunday, May 12, at Tsushido Beach in Shonan, Japan, and the T-shirt in front of me had five names already scrawled on it in heavy black marker pen: Mark Richards, Shaun, Michael Ho . . . all surfers he had seen in Free Ride or in the dozens of American surfing magazines he had studied religiously over the years of his surfing life.

"I like saahfing choob like Flee Lide." He spoke slowly and hesitantly as he offered his T-shirt for my signature. It was my first journey into the heart of the Japanese surfing experience, and my first face-to-face contact with the fans' passion that stokes this surfing community.

I asked the kid what he would do with the T-shirt when the day was over. He answered in proud but broken English that this shirt was a highly valuable artifact, and that he would be pinning it to his bedroom wall, apparently right next to his Pipeline poster of Gerry Lopez. I signed. He said, "Sank you," adjusted his personally autographed Mark Richards cap, and then disappeared toward the judges stand to pick up on more action.

At that end of the beach it looked like things were warming up. Doji Osaka, Japan's resident MC, was busy auctioning two of Shaun's personal surfboards over the loudspeaker.

This was supposed to be the first day of the Japan Surfing Promotion pro tournament — and thousands had descended to the beaches for the spectacle — but there was no'surf. No that it mattered of course, because according to my interpreter, the stars were there, which was most important. There were autographs to track down, pictures to take, and later on an "exhibition surf," and of course there were all kinds of side shows like bidding on Shaun's surfboards.

I was in mild shock. It's hard to believe that such enthusiasm for anything could reach these dizzying heights. The autograph business I can vaguely understand, as they're big on celebrity consciousness in Japan. But when I look out towards the ocean and see all these people sitting on their surfboards—this mystifies me. The surf is flat. Not one foot or one-to-two feet, but flat. In fact, from where I am sitting it looks as though it's almost concave, save for the very occasional six-inch shorebreaker that winds down the beach. And it's crowded! Stretching down the coast, all you can see is surfers, hundreds and hundreds of surfers, sitting in large clumps, occasionally paddling for a wave that by some freak of nature looks like it has an outside chance of breaking—which in Japan makes it good enough reason to paddle like hell because you never know how long the next lull could be.

Jesus, I thought to myself, we talk about "crowds" and "dropping in," and shall I use my big board today, and this swell is junk and that swell is clean—there is a degree of choice in the matter. But these poor bastards talk about the surf in terms of whether it breaks or not! If it's breaking its happening, and you get down there FAST, because a swell can come up and go down so quickly, you might just go for lunch and come back and find the show is over. Which of course could be the ultimate bad move, because who knows when the next swell will come up! It could be days, it could even be weeks. And weeks of living against these impossible odds is not what I would recommend for any average law-abiding citizen . . . but more of this later.

* * *

Right now, sitting on the beach on this warm, humid Sunday, I've come to the conclusion that the Japanese have a massive inferiority complex about their surfing. Maybe it's the lack of quality waves, or the lack of quality surfers, or maybe it's because everything is so small or because it's all such a brand-new buzz for these people. Whatever it is, these kids are literally possessed by the Overseas Star Syndrome. It seems like the entire surfing experience in Japan is based on a fantasy created by movies, magazines, and visiting surf stars. Well, at least it's hard to avoid that logic, seeing that little surf actually reaches these shores. How else can they get so pumped?

While Japan has had surfers for around fifteen years or so, it's only now that this eastern archipelago is making its formal entrance into the international surfing community. And that entrance has been welcomed from all quarters not the least of reasons being that anybody who is anybody in the surfing industry has found a lucrative and enthusiastic new market in Japan. That much is obvious. From where I'm sitting, I can see just about every heavyweight in the pro ranks actively engaged in signing something, and I assure you, it's not being done for fun. A quick look along the racks inside any Japanese surf shop and you'll realize that nobody is out here to discover the surf and sights of Japan. In fact, the average Japanese surf shop comes about as close to being a pro surfers' supermarket as we are ever likely to see. Aside from the usual surfboard models, endorsed clothing, land other paraphernalia, you can buy surfers' colognes and "musk oils" and protein drinks to be "consumed before each surf." And if you're really feeling down, you can even write a pen pal with a Shaun Tomson postcard. No one ever doubted that this marvelous turnout of IPS talent has more to do with dollars, cents, and rating points than it does with anything else.

As a surfing nation, Japan has risen from obscurity to prominence in one short season, and some say it is a prominence based purely on the fact that the Japanese have money to spend in America—which is not entirely true, although the Japanese are aware they I still have dues to pay, and they're willing to learn. They are good listeners and keen watchers, and while right now everyone's lunging for a slice of the economic pie, that situation is only temporary. These guys don't play to lose, and judging from their industrial track record, this country of workaholics should have no problem dealing with a community of leisure junkies such as California.

On the evening of May 3, I was standing in line to board a boat for Niijima, one of the outer islands in the Japanese chain. It was a warm evening and the dock was crowded. People were standing back-to-back waiting to board the various boats headed for one or the other of the islands. But what disturbed me was that it looked like there were at least a thousand board-toting surfers crammed in the embarkation area, and only one island was sporting any action this weekend, and that was Niijima.

This was going to be one hell of a boat trip—an eight-hour blitzkrieg night-ride to an obscure, rural island, arriving just in time for a dawn attack on the two-footers. This was the plan as I saw it from the boatyard. But first, there was the problem of getting on board this craft efficiently, because according to my sources, this boat had limited sleeping space, and if you were unlucky, you could end up on the floor on deck all night, which as far as I was concerned was totally out of the question.

I looked over to my left and noticed Shaun speaking to Simon Anderson. Shaun was being continually interrupted. He would speak for a minute or so, then stop and pose for a photograph, or shake a kid's hand, and then continue speaking. Shaun looked different. Most people were wearing standard surf garb: sneakers, sweaters, jeans—functionalism being the key word. Among this lot, Shaun looked like he'd just finished up an evening at Studio 54: unstructured jacket, Dior shirt, Sason trousers, leather shoes—very High Fashion. We talk about things past and present. He tells me he did a Sprite commercial with Candice Bergen. He says she looks as good as she does in the movies. No, he didn't get her phone number. Yes, the acting business brings good money. No, I'm not exactly sure what I'm doing here right now—which was true, because the "all aboard" whistle had gone and I could see my party deep in the midst of the stampede, moving quickly toward the gangplank.

Later that evening, I was discussing Niijima with my interpreter, who said that the island was the most consistent wave area in Japan. Making a trip to Niijima meant you were hardcore, he said. The place had WAVES and it had JUICE, no Mickey Mouse hodads crowding it out, no Tokyo Joes out to score a couple of chicks with a smart car, a packet of Marlboros, and a new board on the roof. This place was for real, he said.

To me it all sounded wonderful. This was the same rap I give people who have never seen J-Bay before, and all things considered, I suppose it would be fair to say that Niijima is to the Japanese what Jeffrey's is to the South Africans and the Ranch is to the Californians, except of course that the waves aren't quite as good.

Niijima was the site of the first tournament of the Japanese leg: The Japan Surfing Organization's "Super Surfing in Niijima," its official title. Not much of real significance happened in this contest, except that Mark Richards won (making his record of wins a formidable three out of four on this year's circuit) and Cheyne Horan saw a shark in his semifinal heat against Richards and left the water. This incident was a cause for much guffawing among the Aussies, since many were convinced that Horan did see a shark but that it was riding a twin-fin and came all the way from Newcastle, Australia. But only Cheyne Horan knows the truth about that one.

Contrary to my expectations, the surf wasn't much good at all during our five-day stretch at Niijima—not that I was expecting it to be perfect, but aside from the marvelous hospitality of the people, I was genuinely hoping for a bonus: maybe just a couple of days of four-foot makable waves that would keep us in touch with how things are under more normal circumstances.

This was my state of mind around May 8. Around May 28, however, things had changed radically. After two weeks in the Tokyo area, I was beginning to understand how the Japanese could think of Niijima the way I thought about Jeffrey's Bay. It's all relative, you see. As I waved a cheerful good-bye to Niijima, I had no idea I would be wishing for a speedy return.

We were being shipped to Shonan, the largest surfing area in Japan and headquarters for the surfing industry. Shonan is situated in an enormous bay, which all but prevents any available swell from reaching its beaches. And this was where we were to be confined for the following four weeks!

The two contests held in the Shonan area proved to me that you can have international contests when the waves are less than a foot high. The Japan Surfing Promotions event was held in surf so small it allowed for only one turn before fins could be heard scraping the sand in the shorebreak. Peter Townend broke the world record for riding the smallest wave—it was the same height as the thickness of his board: four inches.

That said, the competition in Japan was more physical than I have seen it. Not only was there contact in the waves, there was also contact on the beach, particularly in the last few weeks of our six-week stay. It was around the time of the fourth contest at Chiba that the vibe hit a quivering, scorching peak. The stress levels among competitors must have been to up to absolute maximum, because the mood was distinctly aggressive. Personally, I attributed it all to Road Illness, a terrible disease of the mind that attacks tired travelers.

There is a certain weariness attached to life on the road. Jackson Browne called it Running on Empty, and mid way through our stay in Japan, the meaning of these words were never clearer. I don't care who's paying the bills, living in a hotel room day in and day out gives you the feeling your life is parked in a towaway zone. Most people think pro surfers lead some kind of sun-drenched life of glamor and glitz. They entertain the notion that traveling abroad is always a big fat holiday—it doesn't matter what you're traveling for, you're traveling, and that's bloody well good enough. They don't seem to realize that at times it can actually be a drag. In fact, as far as I'm concerned, this occupation has as many king-shit down and out bummers as any other—which is probably the way PT and Rabbit felt the night before the start of the Chiba contest, after one heated argument too many very nearly resulted in a punchout between the two veteran campaigners.

Here was a classic manifestation of the Illness. Whatever the underlying motivation, a situation nearly arose in which two of the sport's most notable athletes and spokesmen, both of them world champions, reduced themselves to duking it out in front of an audience including contest officials, contestants, and sponsors. But it didn't matter at that stage. Nothing mattered at all, in fact, because we were marching into the SIXTH WEEK in this place, and that was enough to excuse anyone's insane behavior.

Maybe not being able to read dinner menus or road signs or have conversations on a day-to-day basis had something to do with it. Maybe it's because the baths are three feet long and three feet deep and the toilets are just holes cut in the floor without seats (strange at first, but good for practicing quasimodos, and good for the abdomen I think someone said). Maybe the food? Seaweed soup, raw fish, and squid still flinching on the plate? Or maybe it's the pollution on the beaches or the fact that you can't go surfing because there aren't any waves. Actually, the incidents I witnessed probably result from a combination of all these things. I have always held the opinion that a life without waves is sure to drive any bunch of surfers to reckless and foul deeds, and it can only be worse in a place like Japan, where culture shock is scrawled across the forehead of every male Caucasian visitor on this tour. In my years of competitive surfing, I've seen my share of table dancing and assorted blind, twisted outrageousness, but this was an education.

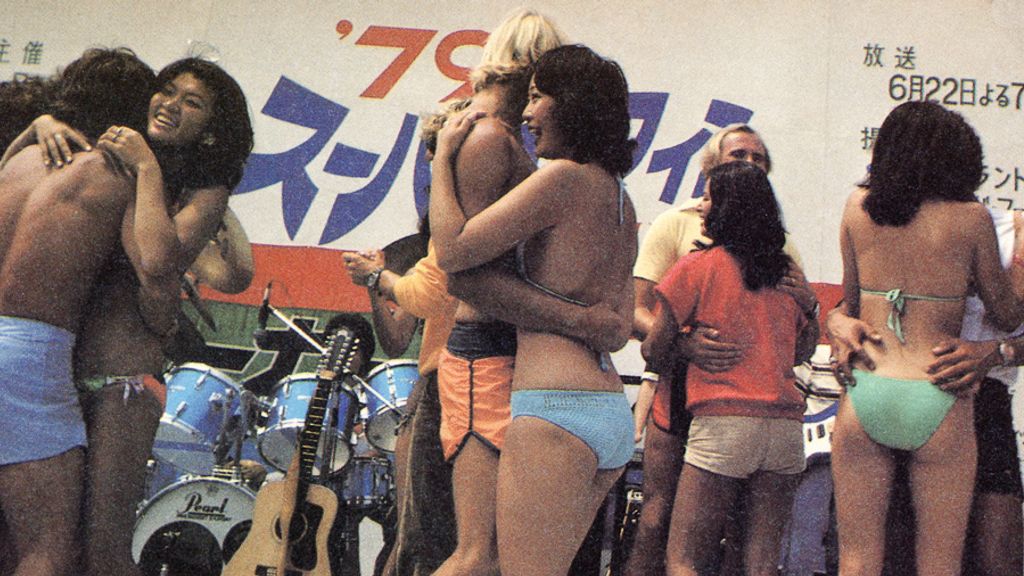

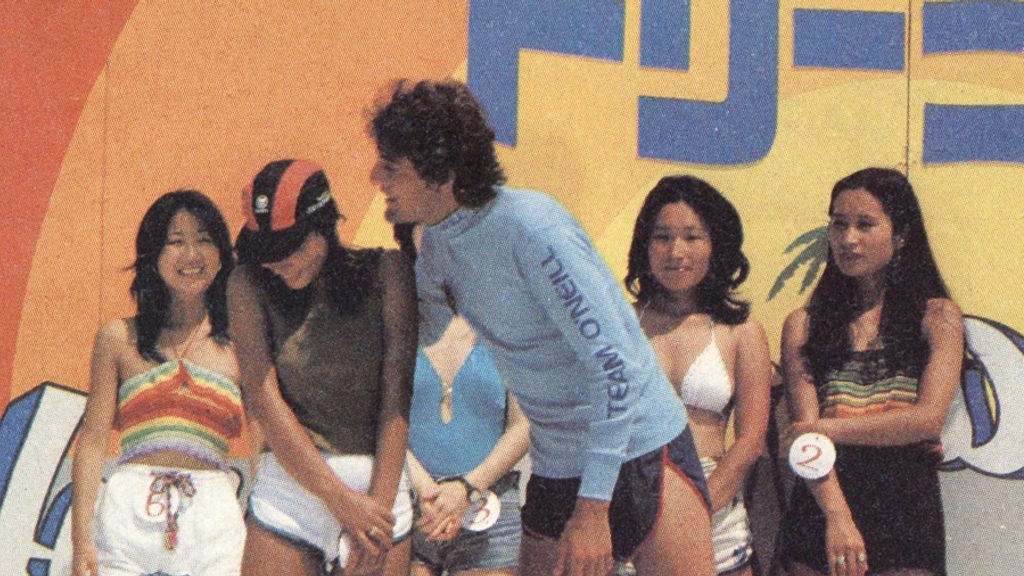

The Chiba event was a good example. Officials had organized a Miss Chiba contest as a sideshow for spectators. Normally, most surfers observe beauty contests and other disco trivia from a cool distance. But this time, the surfers in the event would select girls off the beach and offer them as entrants. This kind of schlock entertainment is supposedly diversionary, just a break from the tedium of watching ten heats in a row, except this time everyone was totally into it. It was midday, a band was playing, and a dozen or so of the world's best surfers were dancing on the goddamn stage, and this was before the contest was even over! It could have been real Gong Show material were it not for the fact that everyone was having such a great time.

This couldn't happen anywhere else. The Japanese are oblivious to the archetype roles of surfers in a Western Culture. They don't know anything about the antiheroic, antimaterialistic California Freedom Rider. To them, surfing with a clear board and a black wetsuit is exactly how NOT to be Cool, and this happy melee on stage was a quite normal state of affairs, just as it's quite normal to wear a full wetsuit with crimson sleeves and pink legs, or something similar, that the locals at Oxnard would consider falling into the category Beyond Star Wars and hence worthy of destruction.

I first noticed traces of Road Illness weeks earlier in Shonan. After it had been flat for twelve days, I remember seeing Critter Byrne wandering around the streets talking very seriously to himself. He was later reported being seen throwing his boards against a cement wall. This was disturbing: I had thought something was weird in my behavior, but I wasn't sure, and I must admit I was relieved when I saw Crit acting this way. It wasn't just me.

Sitting in the car on the way to Tokyo for surf-shop promotions, I used to think deeply about Road Illness. What caused this horrid disease? There was no doubt that everyone had contracted it, some worse than others. Forgive me if I harp on this question of sanity, but it seemed so central to everything in Japan that even these promotions had an element of absurdity to them. We would leave around 4 p.m., spend three hours in the traffic, get there around seven, do autographs for an hour or so, eat, and then get dangerously drunk. It was an evil cycle I knew I should break out of, but what can you say to these kids, save for scant simplicities? After an hour or so, you're fresh out of things like "Pipeline very BIG and very STRONG!" Conversation dries up-and you resort to booze to bridge the gap, particularly if it's a female you're talking to.

Anyway, on one particular trip into Tokyo, Jackie Dunn was sitting beside me in the car during one of my psychic wanderings about the Illness. He had the window open and was breathing deeply in the traffic fumes and saying things like "Mmmm, tastes good" and "Feels great," and then suddenly, without warning, he would lurch toward the window and scream at a passing woman. I thought to myself, "Shit, this bastard's gone and forgotten." Not that I minded his demented antics inside the car, but we were in the middle of Tokyo, asphyxiated by fumes and crawling in five-mile-an-hour traffic, so if Jackie, in one of his spasms, happened to lean out the window and scream at Bruce Lee's girlfriend, there would be no escape from Bruce Lee. He would simply rip the doors off and beat the hell out of us.

But besides this, Jackie's voice at full pitch comes close to breaking glass. In fact, I'm convinced that a two-hour recording of a JD monologue would be a most provocative torture device under the right circumstances. But not now, for God sakes. "You're sick," I yelled, "you're 'round the bloody twist." He laughed and replied, "You gotta understand, I've been on the road four months now and I'm cracked. It's temporary, I suppose, but what can I do?"

He had that wild idiotic grin, which I remember struck terror in the heart of a young Japanese wench one night at a party. He had moved toward her like a guided missile, not leaving until the poor girl burst out crying.

* * *

I'm not sure to what extent the Japanese surfers appreciate it, but pollution is this surfing community's biggest threat. Traditionally, the Japanese have had little use for the ocean as a recreational area, and it shows. The beaches in Shonan are heavily polluted—knee-deep in some places—and show almost a flagrant disregard for even the most basic principles of environmental protection. Shaun told me he wears boots when he surfs only because he doesn't want to stand barefoot in the sand. He said he couldn't face the prospect of his skin making contact with "this filth." Not that I blame him, of course; there could be sixteen kinds of scurvy and gangrene lurking in that slime, not to mention the water. Jesus, the water is so full of scum it actually radiates gases! I had a recurring nightmare about plutonium waste deposits circulating the waters around Shonan. I kept dreaming that when I woke up I'd find my body had gone through some terrible mutation caused by a chemical inducted into my system when I was surfing. Ah yes, that's the part about Japan my tourist brochure never discussed. They prefer to talk about the Japanese hospitality instead, which incidentally is of the finest in the world.

Yet when I think of Japan, I think of what it means to be enthusiastic. A strange feeling came over me that day when I saw hundreds of surfers sitting out there in a flat ocean waiting for the imaginary Free Ride peeling through the oceans of their minds. How long can this Big Boom keep spinning? How long can these guys keep up this level of sheer unadulterated stoke without becoming jaded and worn like a lot of us out here in the "real world"? Now there's something: l once asked my interpreter to translate the word "stoked" into Japanese, and he said there wasn't such a word. I was amazed.

This place was some trip: With that many people living in such a small area, just the act of going surfing would have to be one of the most intense highs on the market, wouldn't it? We were driving along the coast highway one gray afternoon. The surf was crowded as usual. I chuckled to myself and pushed a cassette into the tape player. Graham Parker came howling through the speakers:

When after all the urges,

some kind of truth emerges.

We felt those deadly surges,

discovering Japan.

[All photos by Denjiro Sato]