SUNDAY JOINT, 2-4-2024: REVIEWERS SAID WILT CHAMBERLAIN’S SURF MOVIE WAS AN AIRBALL. WAS IT?

Hey All,

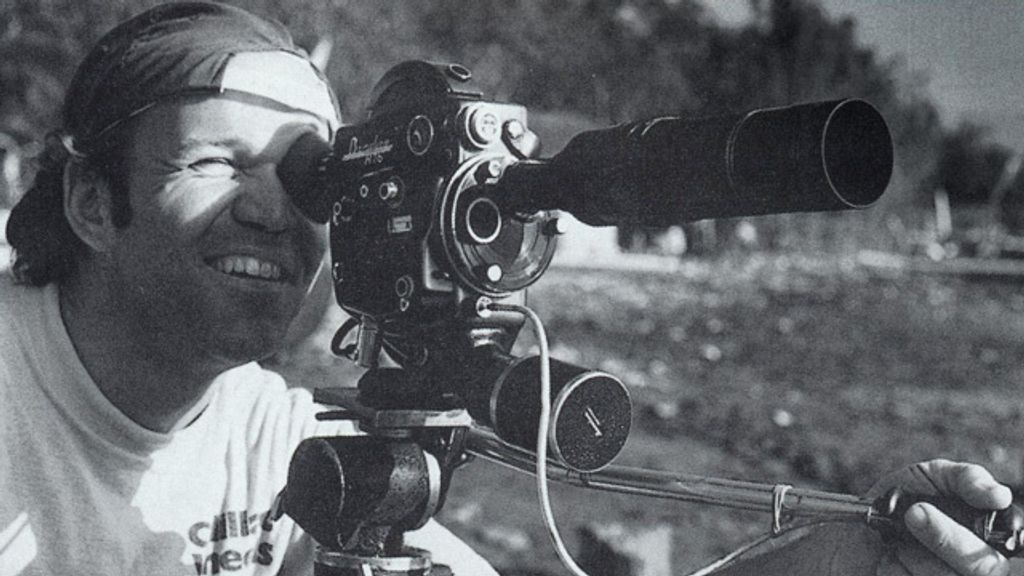

Los Angeles-born surf filmmaker Hal Jepsen was the Taylor Steele of his era, or the other way around. The right guy in the right place at the right time. Jepsen’s Cosmic Children(1970) equals Steele’s Momentum(1992), is what I’m trying to say—both movies are raw and artless and as bleeding-edge as you could get in a pre-internet age in terms of showing us what was happening almost as it happened. Surf films that came out around the same time as Cosmic Children and Momentum, by comparison, looked dated on arrival. (Jepsen’s movie is better than Steele’s, for my money, not just because Hal at least stuck a few lines of rudimentary narration in there but because he went full steal-it-to-feel-it on the soundtrack, and his grainy semi-focused film is carried along by the Stones, Hendrix, BB King, Dave Brubeck, and Cream.)

Jepsen followed up with two more hardcore self-funded movies, A Sea for Yourself (1973) and Super Session (1975), then swung for the fences with a 1976 all-in mainstream-targeted surf-ski-skateboard-hang-glide-etc film called Go For It, which most definitely did not become the new Endless Summer, as hoped for, but did give surfing a collab for the ages, as it was funded and coproduced by retired NBA legend Wilt Chamberlain.

A surf-based film made by a black seven-foot Philadephia-born basketball player with four MVPs and a pair of championship titles to go with his untouchable and still-mind-boggling 100-point single-game scoring record, was actually not as bizarre as it sounds. Chamberlain moved to LA in 1968 to play for the Lakers, loved everything about the city, sun and sand included, and after his 1973 NBA retirement, focused his still-considerable athletic talents on volleyball, both indoor and beach. Too slow for two-man, Wilt became a fixture on the six-man circuit, and I’d see him often during tournaments at Manhattan Beach; the man was absolutely on a mission, sweating rivers, loud and talkative, sand-diving, game after game, happy and relentless.

Where and when Chamberlain met Jepsen—who knows. Hal was personable and easygoing and knew everyone who mattered in what was not yet called the action-sports media game, but he was also pretty hapless. A few years ago I talked with fellow surf-filmmaker Scott Dittrich about Hal.

You got started in movies working with Jepsen?

I did. He was working on A Sea for Yourself when I met him. Around 1971. He was living in Topanga, right off PCH, and he was . . . let’s say a bit disorganized. He needed help on the business end, so I organized showings, booked the theaters, delivered the film, that kind of thing.

Did you get everything in order?

Well, you know, it was the ’70s and there was a lot of substance stuff going around, and that didn’t help the organizational side.

But the film came out as planned?

Kind of. Actually, no. It got postponed several times. But finally we booked the Santa Monica Civic for the premier, and on opening night—the movie wasn’t really finished. Mostly it was just a work print. Part of the movie was finished, and part was still really rough. It had some issues, put it that way. We’d been up for three days straight before the Civic show, working on the movie, doing promo, and the clock was just ticking. It was nuts.

How’d it go over on opening night?

The audience could tell. They weren’t happy.

Hal get pelted with food and bottles or anything like that?

No, no. Nothing violent. Just this disappointment. You could feel it in the theater. Cosmic Children had been such a hit, and people were really expecting something great. A Sea for Yourself actually got better later in the year, because Hal was editing it between screenings.

On the other hand, like I say, Jepsen was a wellspring of good cheer, plus, amazingly, he had a UCLA business degree, and I’m guessing those two things alone were enough for Wilt. They teamed up, hired a director, found a distributor, and banged out Go For It in less than a year. They were gunning for an updated Endless Summer-style crossover hit. What they got instead was an earnest try-hard coat-of-many-colors fail. If you looked close enough and parsed carefully there were a few bright spots in the Go For It reviews, but the film was mostly savaged. The LA Times review, which ran next to the Adult Movies ads (Deep Throat was still playing at the Pussycat, four years after it’s debut), called Go For It “extremely repetitious,” while the Detroit Free Press said it looked as though it was “put together in a meat grinder,” and that “it may just force Chamberlain back to the court to recoup.”

Go For It was a quiet little box-office flop.

I missed the film when it came out, saw it for the first time this week, and would say the reviewers and not-interested moviegoing public got it right. Except for one thing. The opening half of Go For It has a long section on skateboarding, as does the second half. The first, I’m nearly sure, was shot by Jepsen. It’s fine, very surf-movie-ish, we get Larry Bertlemann and Tony Alva and many other mid-’70s shredders; the photography is sharp and colorful with lots of super-tight-angle fisheye slow motion, the wipeouts are gnarly, so no real complaints. The segment is all thrust and no depth, though, kinetic without going anywhere, and closes with a sound-effects-boosted comedy bit that falls flatter than the ’75-’76 Virginia Squires win-loss record.

But the next skateboard sequence in Go For It is a different matter altogether. The entire 12-minute piece is filmed at the Ventura Skateboard Championships, and while it’s not a documentary, exactly, the detail is sharp, the editing snaps together perfectly, and the camera somehow takes us deep into the personal space of contestants, organizers, and spectators alike. Some genuine film alchemy takes place here. What we see is fun and spiky at the same time. You’re smiling at the jury-rigged barefoot DIY-ness of it all but there is a hum of tension, during the first two-thirds anyway—helped along by the frequent crack of a starter’s pistol in the background as slalom and downhill skaters launch one after the other—and we ride that edginess as much or more than we ride along with the action itself. On one hand, nothing much is at stake. No prize money or ratings points. But this funky little contest in the barely-developed hills above Ventura means the world to everyone in attendance, and delivering that jittery hyperfocused mood to the screen puts this one sequence in a different order of filmmaking altogether—not just in terms of what else we get in Go For It, but any other surf movie made to this time, or maybe any time. I watched it twice, back to back.

Look for Peter Fonda cheering on the sidelines!

Thanks, everyone, and see you next week!

Matt

PS: Two years later we get Skateboard: the Movie, with Leif Garrett. Apples and oranges, I guess, but it feels to me like skateboard coolness by this point is already in retreat.

PPS: Wilt Chamberlain’s stay-in-the-game stamina as a ballplayer is second only to his reputation as a bed-hopper. Go For It brought out the opposite in him—as a movie producer, Wilt was one and done.

[Photo grid, clockwise from top left: hang-gliding in Go For It; Wilt Chamberlain; skiing in Go For It; Larry Bertlemann from Hal Jepsen’s 1975 film Super Session; art from Go For It poster; tandem skateboarding. Frame grabs from Cosmic Children. Wilt Chamberlain in Manhattan Beach. Hal Jepsen behind the camera. Peter Fonda at the 1976 Ventura Skateboard Championships.]