SUNDAY JOINT, 2-6-2022: OUR MOST SUPREME PLEASURE

Hey All,

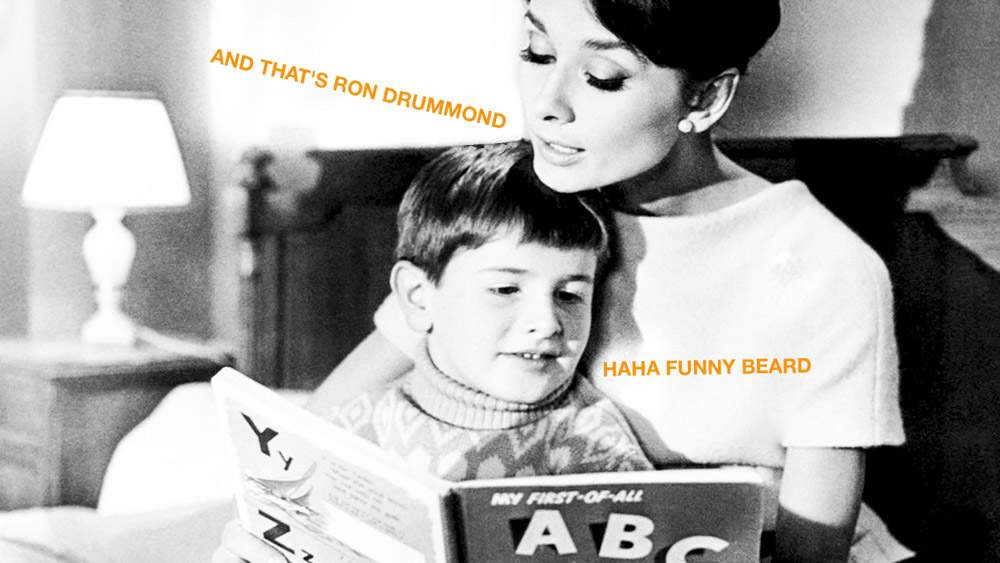

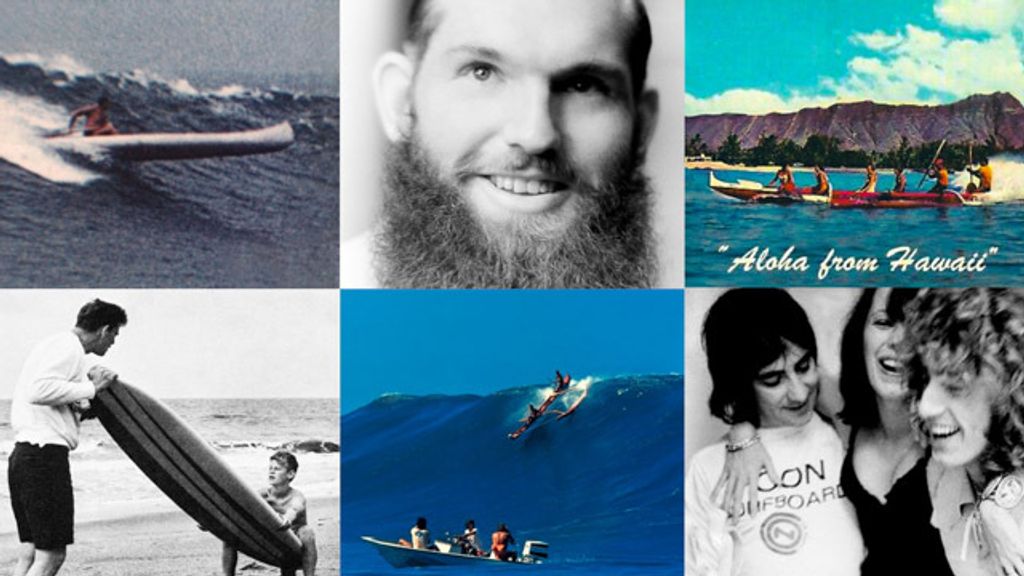

Canoe surfing doesn’t have much middle ground, in terms of how it is performed. Easy and safe on one side. Reckless and horrifying on the other. This wasn’t always the case. Back when we wore coonskin caps and hummed Patti Page songs while walking uphill to and from school, Ron Drummond was canoe surfing on the regular at Dana Point, in waves from two- to 12-feet, having a great time while putting everybody else in the lineup at risk of a canoe-administered blunt-trauma visit to the ER. There was no canoe surfing fad in California. Drummond was just one man, doing what he loved—but my god what a man.

Drummond aside, canoe surfing in modern times is most often performed in the velvety sit-back-and-relax nearshore waters of Waikiki, just out from the Royal Hawaiian, where, for $300 and a signed waiver (plus tip for your steersperson), you and up to five friends can climb into an outrigger to enjoy the world’s smoothest and easiest wave-riding experience—and thus follow in the happy plumeria-scented wake of Babe Ruth and Shirley Temple and 10,000 other celebrity surf-tourists. This everyday form of canoe surfing is so deep in the background of our wave-riding world that it does not register.

Way over on the other end of the spectrum, you have big-wave canoe surfing, which is really more of a stunt than a thing. It happened with Project Avalanche in 1981, and recently at Waimea (watch here), and the Makaha crew will slide the Bowl on occasion. On second thought, big-wave canoe surfing is spectacular enough to grab our attention, so while it is rare, it is very much a thing as much as it is a stunt.

Before leaving the topic, let’s detour to the 18th-century and William Anderson, ship’s surgeon for Captain Cook’s third voyage to the South Pacific. In a Tahiti-penned journal entry from 1777, Anderson begins by describing the local flair for human torture (eyeball-scooping included), then pivots smartly to “what can give them pleasure and ease,” which in turn leads to the first best-written account of recreational wave-riding.

On walking one day about Matavai Point . . . I saw a man paddling in a small canoe so quickly, and looking about with such eagerness, on each side, as to command all my attention. He went out from the shore, till he was near the place where the swell begins to take its rise; and watching its first motion very attentively, paddled before it, with great quickness, till he found that it overtook him, and had acquired sufficient force to carry his canoe before it, without passing underneath. He then sat motionless, and was carried along at the same swift rate as the wave, till it landed him upon the beach. Then he went in search of another swell. I could not help concluding that this man felt the most supreme pleasure, while he was driven on so fast and so smoothly, by the sea.

Read the full excerpt here.

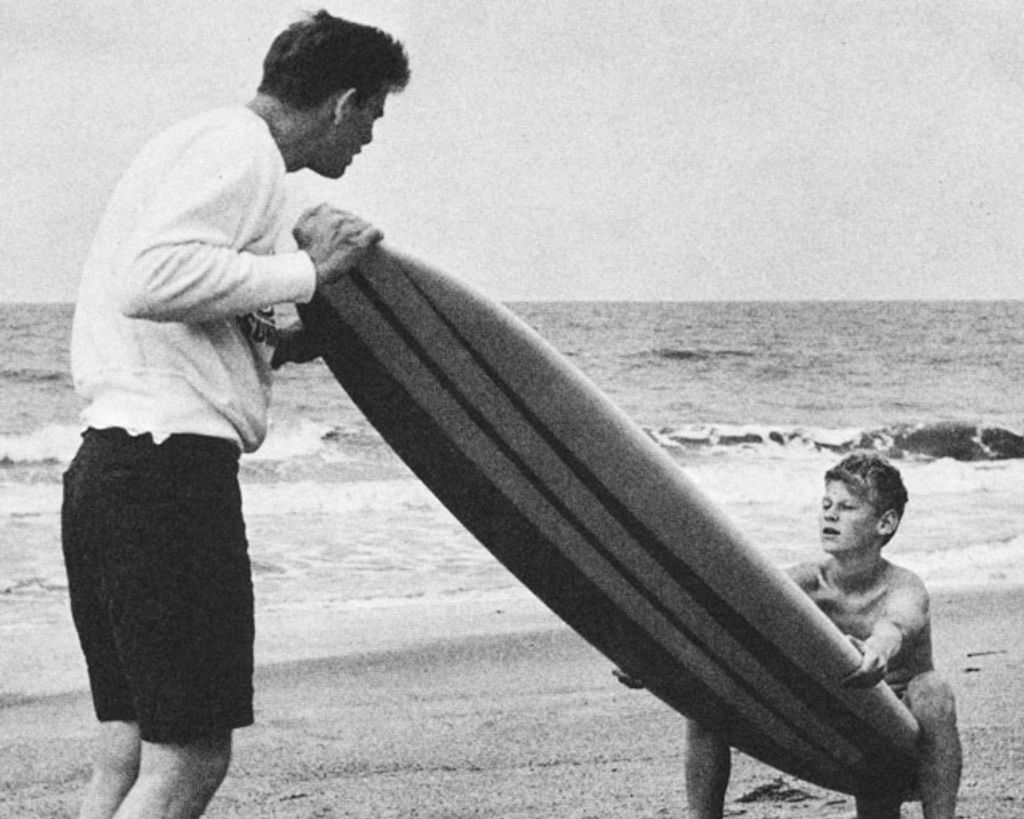

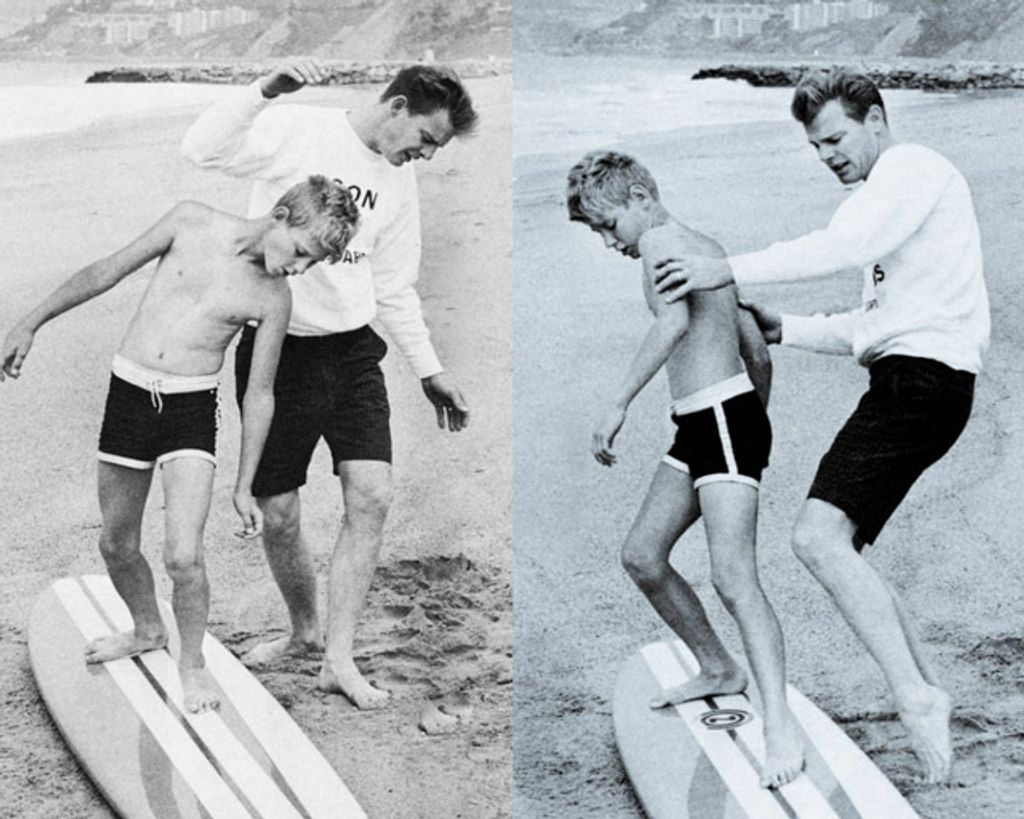

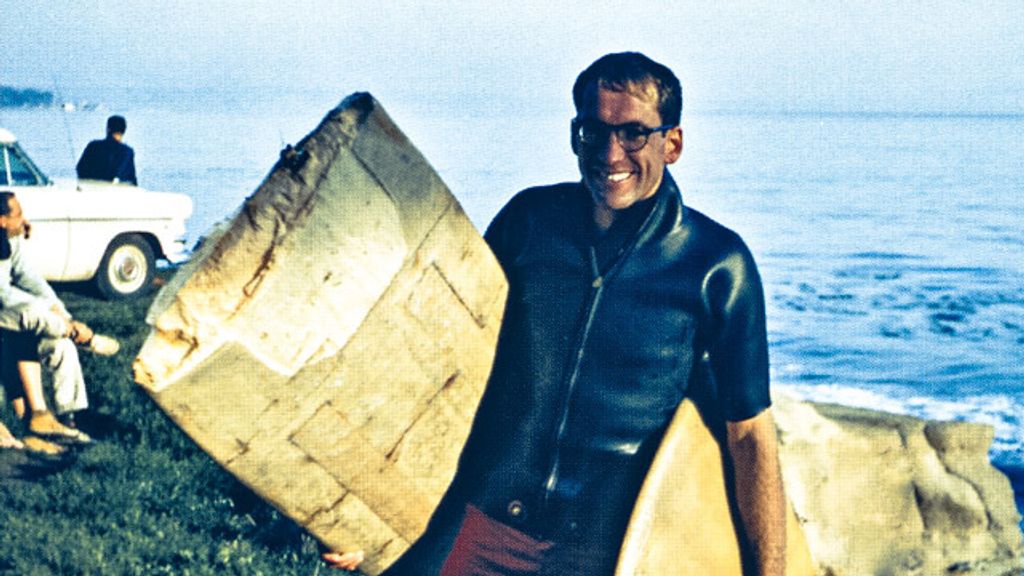

Surfboard maker Con Colburn died fairly young (in 1991, of lung cancer, at age 57) and thus didn’t have the opportunity given to most of his fellow Golden Age boardmakers to shore up his legacy. Because of this, and because he was a private person to begin with, Colburn himself has vanished behind his famous Con Surfboards bullseye logo like the Cheshire Cat disappearing behind his smile. So I was glad to find a dozen or so photos of Colburn in a 1965 how-to book titled The Young Sportsman’s Guide to Surfing.

I posted a longer entry on Guide, with more photos (click here), but wanted to bring the last few paragraphs front and center:

By far, the best part of the book is the how-to photos, taken by Chan Bush and shot on a grey-sky beach just north of Santa Monica. The same two people are featured in each shot: an adult surfer (Con Colburn) giving instructions to a tousle-haired boy who looks about 12. The shots are well framed and composed. But something else caught and held my attention and it took a moment to zero in on what it was—the seriousness both people are bringing to the task. No smiles. No false encouragement. What Colburn and his student are doing is a different thing altogether than the fun-fun-fun version of surfing the Beach Boys sing about.

No doubt this has a lot to do with the fact that the sport at this point in time was trying mightily to shake off the beach-hooligan rep it had earned over the previous ten years. But on top of that, by luck or design, the photos also get to an overlooked truth about surfing, which is that the fun part is mostly found on the perimeter. Driving with friends to go surf is fun. Hanging out on the beach afterward is fun. Almost everything having to do with actually riding waves—especially at the beginning—is difficult. Really, endlessly hard. But the good kind of hard, the addictive kind, with achievements small and large that scroll out for years or decades, and peak flow-state moments that you will be smiling over on your deathbed.

But, kid, each of those moments will cost you hundreds of hours of time and attention. Have fun on the way, sure. But Uncle Con here, with that stern look on his puss, is doing you a favor. Pay attention. Take it seriously.

“Don’t treat it like a toy”—the Beach Boys got that part right.

Thanks for reading, everybody, and see you next week.

Matt

PS: I’ve just found out that Peter Cole, the long-limbed big-wave surfer/scholar/gentleman who alongside Pat Curren sat way out the back and rode the biggest Waimea Bay had to offer, has died at age 91. Cole was a Surfing Everyman—maybe the greatest of them all. Except he was 40 IQ points smarter than average, and wholly comfortable in his own skin. Peter wasn’t like us, in other words. He was who we wanted to be, not just as a surfer but as a person. The opening shot of this video shows Cole driving along a shady highway in Santa Cruz just as a passing thought puts a small half-smile on his face. Peter could be passionate and emotional, and fought for things he believed in. But he was never far from the centeredness that we see on that Santa Cruz highway, and if somebody tells me he died with that same calm half-smile, nothing would surprise me less.

[Photo grid, clockwise from top left: Ron Drummond at Dana Point, Drummond during his pro wrestling days, 1950s Waikiki postcard, Keith Moon in Con Surfboard T-shirt, Project Avalanche photo by Steve Wilkings, Col Colburn giving surf lesson. Eighteenth-century engraving of Hawaiian canoe paddlers. More Colburn. Cole dropping in at Sunset in 1961 by LeRoy Grannis. Color Peter Cole photo with broken board in 1957.]