SUNDAY JOINT, 3-26-2023: À VOSSA SAÚDE! AND CAIPIRINHAS FOR EVERYONE

Hey All,

Correcting surf history misconceptions is great just for the neener-neener I-fixed-it pointy-headed rush, and I’ll be chasing that high till I’m soul-arching past the Pearly Gates on my way to an afternoon meetup with Tubesteak and Rell Sunn. But it also feels great because installing a new bit of history, apart from moving the ball a bit further downfield in terms of truth, more often than not also means you’ve found a richer, more colorful, more dynamic version of history than the one being replaced. Win-win, as Herodotus was always saying.

Such is the case with Brazilian surfing’s origin story.

As discussed a couple of weeks ago, Australia’s Peter Troy did not, as we’ve been led to believe for 50-plus years, bring surfing to Brazil. Troy himself knew this, and wrote with eloquence and cheer about how, in 1965, he unwittingly fell into a Rio de Janeiro surf scene that was a throwback in terms of equipment and technique but otherwise well-established and fired up. “Beyond, a rocky point nestled at a sheltered end of a long beach,” Troy later wrote, describing his first look at Arpoador Beach. “Cars, boys and girls, surfboards by the dozen, sea patrol, and surf. Discovery!”

Troy borrows a board, paddles out to ride a few, impresses everybody, and ends up having dinner and talking board design at the house of a carioca boardmaker. The experience puts Troy in a philosophical mood. “I had encountered a race of humans who thought, acted, lived and believed as I [do]. These Brazilians have developed in an isolated area, and yet with completely similar characteristics [as other surfers].”

Big-picture-wise, this is where it really gets interesting, in that the Arpoador crew, despite being so far removed from all global surf capitals not just by distance, but also language and media, nonetheless clearly shared the same basic surfing DNA as wave-riders from Sydney and LA and Honolulu. The development is just taking place on a different timeline. Boards, for example. By 1959, Rio surfers had come up with what they called the madeirite, a thin round-nosed plank made of marine plywood, and when Troy showed up in 1965, the madeirite was still the only game in town. Why plywood? Insanely high tariffs killed the market for imported foreign-made boards, while modern boardmaking materials—polyurethane foam, resin, fiberglass—were scarce or unavailable or too expensive.

This wasn’t just a Brazilian thing. Cost and access have always determined what boards are made of. So in America, starting in the 1940s, we’ve got glued-up balsa covered in fiberglass, leading to foam and glass in the 1950s. In Hawaii during the 1940s and ’50s, it’s redwood-balsa combos finished in varnish; in Australia it’s cross-braced plywood till ’57, and so on. Global communication, or lack thereof, played into this, too. Surfers in one corner of the world had no idea what was happening in other nations for months or even years at a stretch.

But while you’ve got different materials nation to nation, the object for everybody, everywhere, is the same. Improve board performance. Reduce weight. Add lift here, put some roll there. Almost every new board made during this period was seen as an opportunity to move forward, design-wise, even if just by a tiny bit.

Oh, and because we’re all going to be down there on the beach trying to impress each other, let’s put a little zing into the finish work, too. Nothing tickles the soft flanks of a surf historian’s imagination like the colors and designs of pre-mass-produced boards. The top photo, below, was shot in Rio five years before Peter Troy arrived. The middle photo is LA County around 1958. The bottom shot is Waipu Cove, New Zealand, 1959.

Back to Rio. The original Arpoador surfers, much like the pre-Gidget Malibu crew or the first post-clubbie surfers in Australia, were by and large middle-class kids and young adults (the Brazilians were maybe a little wealthier on average than the surfers in California and Australia) who developed a taste not just for riding waves but for beach-lounging and job-avoiding and all the other happy sun-warmed first-level hedonism associated with the sport. Tito Rosemberg, the best-known madeirite-age surfer outside of Brazil, as he later chaperoned Kevin Naughton and Craig Peterson during one of their famous mid-’70s surf adventures, later had this to say about surfing in Rio—and you can replace the final two words of the passage with the location of your choice (Bondi, Topanga, Cornwall, Gilgo, for starters) and it still works:

We lived the best time in the best place in the world. We were a bunch of rascals. Many were dedicated vagabonds. Our religion was pleasure. We ate badly but we were healthy and we were a tribe—the unproductive people of Arpoador Beach!

Some, thank goodness, occasionally took a break from being unproductive.

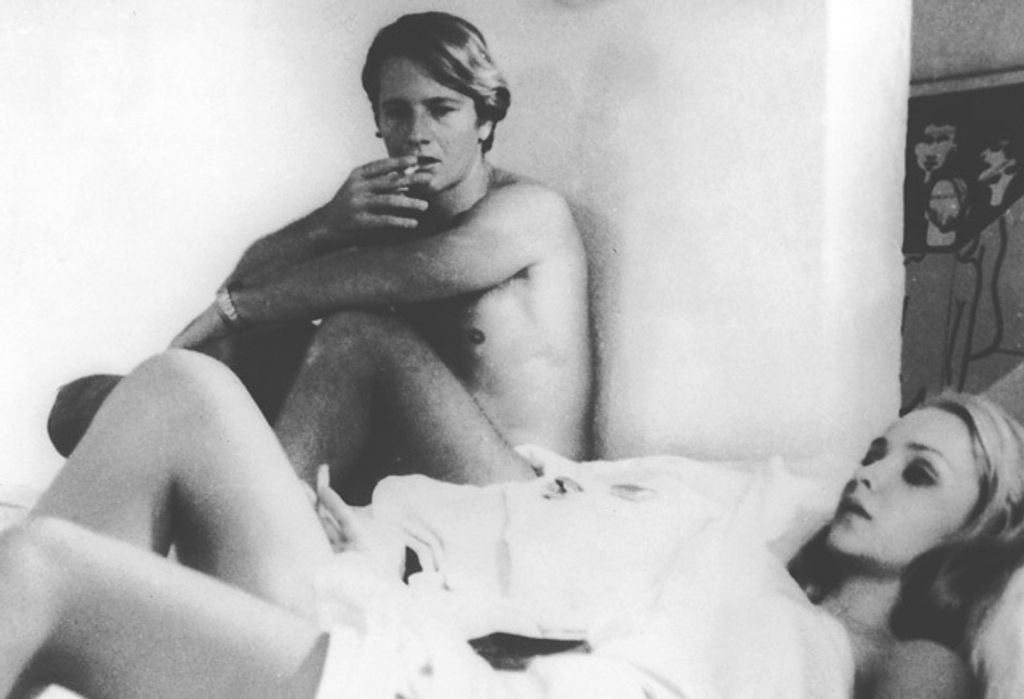

Bossa nova original and Arpoador local Marcos Valle, for example, wrote and recorded “Surfin’ in Rio” more or less around the time Peter Troy was in town. Sylvia Telles does a great version, and I love that while she’s out there riding waves at “20, 30, 40 miles per hour, going more, more, more!” her boy-toy is waiting on the beach, instead of the other way around. Telles died in a car accident less than a year after recording “Surfin’ in Rio,” and just a few weeks after this amazing performance in Germany with guitarist Rosinha de Valença. Marcos Valle lives and performs to this day; his “Summer Samba” is probably the best-known and most-covered bossa nova song of all time, and if I had a dollar for every time I drank an apres-surf beer to Bebel Gilberto’s version of the song we could cancel next year’s fundraiser. Future cinema novo star Arduíno Colasanti pulled the longest and lustiest glances from everyone on the beach at Arpoador—and everyone in the bars, cafes, streets, too—during Brazilian surfing’s plywood age. That’s Colasanti at the top of the page, in the photo grid, with his pre-madeirite “church door” board (as with Peter Troy, Colasanti is sometimes mistakenly called the first surfer in Brazil), and that’s him below, with teen-dream Adriana Prieto, in the 1966 film El Justicero. Colasanti is best known for starring in 1971’s How Tasty Was My Little Frenchman, in which he is frequently and impressively nude.

Jorge Paulo Lemann, former Davis Cup tennis player and your current #1 richest person in Brazil—Bloomberg once called him “the world’s most interesting billionaire”—later claimed the lessons he gleaned as a hotshot teen surfer at Arpoador were more important to his towering success in investment banking than his Harvard education. “Catching the biggest waves possible, doing the hardest things [in the water],” Lemann told Trip magazine in 2012, “all of this helped me become the entrepreneur I am.”

I’d be remiss as a surf historian to not pass the mic here to dedicated lefty Tito Rosemberg, who believes that Lemann, in becoming an apex-capitalist, betrayed his Arpoador surfing heritage: “He forgot about the waves, the sea, the beach, and even poetry, since money hardens the soul and takes up all your time. Sad fate!”

Commerce vs poetry reminds me that everything we’ve talked about here takes place in the run-up to, and the early years of, Brazil’s 21-year military dictatorship. But that is a topic for another day, another Joint.

Lastly, I can’t sign off without a brief description of what is sometimes described as Brazil’s first national surfing championships, won by Arduino Colasanti. I’ll have to get back to you on the year, but I’m guessing around 1958. Decades later, Colasanti described how the event played out—and this, folks, is why my love for surfing and its glorious past will never die.

It was supposed to be a fishing contest, with a barbecue at somebody’s house scheduled for after. But the sea was choppy and bad for fishing so we went straight to the barbecue. After drinking a lot of caipirinhas we realized that, since there were waves, the championship should be for surfing instead of fishing. We drove to Arpoador with all these girls—it was a party. The winner was picked by general consensus, and I won because I caught the most waves. And also because Jorge Americano—Jorge Paulo Lemann—wasn’t there. And because my girlfriend was a bit of a boss on the beach, and told everyone to vote for me.

Thanks for reading, vá com Deus, and see you next week!

Matt

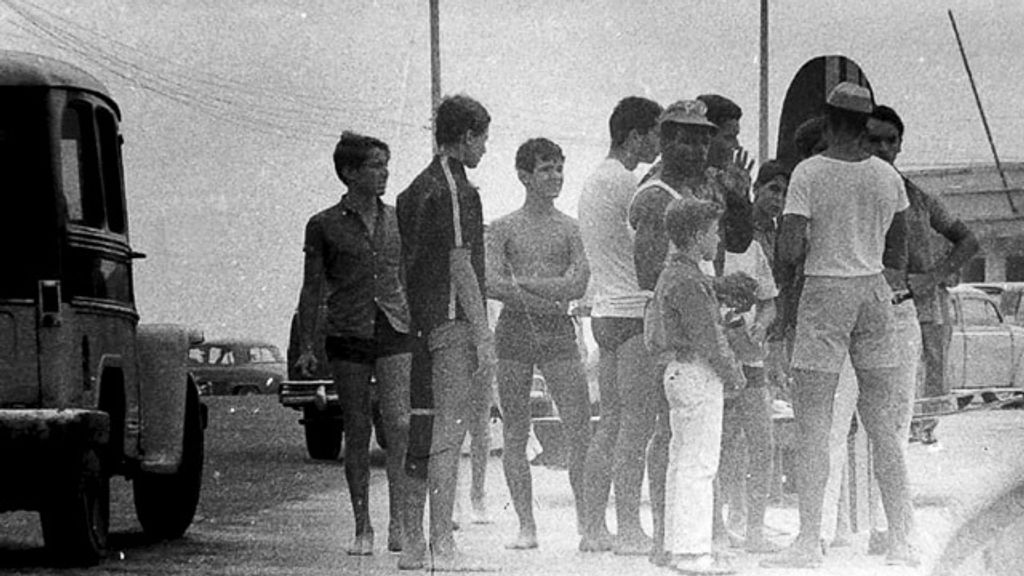

PS: I originally grabbed this Tito Rosemberg photo, taken at Arpoador in 1965, because it gives us another peek at a madeirite board, over there on the right. Then I noticed the white-seamed wetsuit jacket on the surfer to the left, and I cannot stop staring at the beavertail, it is tremendous, the John Holmes of beavertails, the Blind Melon Chitlin’ of beavertails.

[Photo grid, clockwise from top left: Arduíno Colasanti and his church door board; caipirinha; Tito Rosemberg, around 1985; Herodotus; vintage Rio de Janeiro postcard; Sylvia Telles and husband José Cândido, around 1957. Arpoador, mid-1960s. Madeirite-riding surfers at Arpoador, 1963, photo by Tito Rosemberg. Rio surfers, 1960. Framegrab from Gidget, 1959. Surfers at Waipu Cove, New Zealand, 1959. Tom Jobim, Sylvia Telles, Marcos Valle, 1966. Arduíno Colasanti and Adriana Prieto in El Justicero, 1966. Colasanti, center, surfing at Arpoador, photo by Tito Rosemberg. Surfers gathered on sidewalk near Arpoador, photo by Rosemberg. Special thanks to Reinaldo Andraus for the guidance on Brazil's surf history.]