SUNDAY JOINT, 5-16-2021: EMBRACE THE TWANG

Hey All,

Although I’ve paddled out with various country-western songs in my head for 40-plus years now, country music and surfing, for me, exist in two completely different buckets. Blame my SoCal upbringing. Loretta Lynn wasn’t on the KMET playlist. Merle Haggard did not have a place on any of the bootlegged surf movie soundtracks that had me pinned to the rafters at the Santa Monica Civic. I once went down a list of musical genres for Martin Potter, to see which ones he liked, and when I got to country-western he pulled a sour face and just said “Sickening.”

And yet I persisted, and here we are in 2021, and Tyler Mahan Coe’s high-density podcast Cocaine & Rhinestones, on the history of country-western music, feels like my heavenly reward. There is much to love about Rhinestones, but what strikes me again and again is Coe’s utter confidence in himself and his material, and the fact that the show is sprawling almost beyond measure while also fully DIY. Coe is my spirit animal.

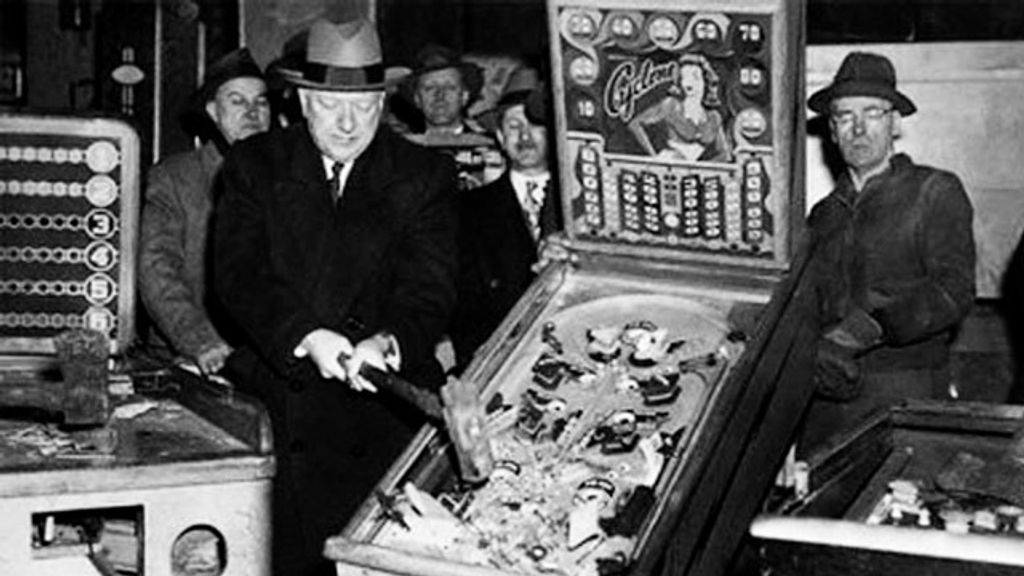

Cocaine and Rhinestone’s first season came out in 14 weekly installments during late 2017 and early 2018. It is excellent but scattershot, with each episode given its own country-centered topic (everything from the Louvin Brothers to “Harper Valley PTA” to Buck Owens), and you can tell Coe is still finding his rhythm and voice. He then went quiet for three years to research and write Season Two, which finally came out last month and ostensibly is about George Jones. I stumbled onto Rhinestones just two weeks ago (thanks to this article), and began with Season Two, Episode One. Coe’s hyper-enunciated speaking style takes some getting used to, but I was hooked from the cold-open intro, which is a ten-minute riff on the early years of pinball machines, back when the game was more punk than 10,000 Mikey Wrights.

No mention whatsoever in the Intro of George Jones.

In fact, I’m now four-plus-hours into Season Two and the Possum is still way off to the side. But who cares? Coe is smart and enthused, a happy destroyer of myths, and bone-dry funny in the bargain, and I am 100% sure he will deliver me to Jones in due time. Meanwhile, the pinball detour was followed by a similar discursion into the queer-in-both-meanings-of-the-word origins of the song “Tutti Frutti,” which spins into a look at the history of refrigeration, which in turn leads to a riff on ice cream’s long journey from 16th-century royal favorite to Baskin-Robbins, which somehow gets us to Roy Acuff singing “Wabash Cannonball” at the Grand Ole Opry. It is head-spinning, to be honest. Relentless. I had to go back and listen to some parts twice, the way I do with Letterkenny episodes, because a lot of it goes right by me on first listen. That said, if we get to the end of Season Two and Coe announces that, surprise, he’s going to put George Jones off till Season Three, I will send him $50 anyway (the show is funded entirely off small donors) and call myself a satisfied customer.

With that forty-acres wind at my back, allow me to introduce you to a long-forgotten Surfing magazine writer and photographer named Mickey Gose, who was born and raised in Oklahoma and lived a life that nutcase outlaw-country singer David Allan Coe—yes, father of Tyler Mahan Coe—should have long ago memorialized in song.

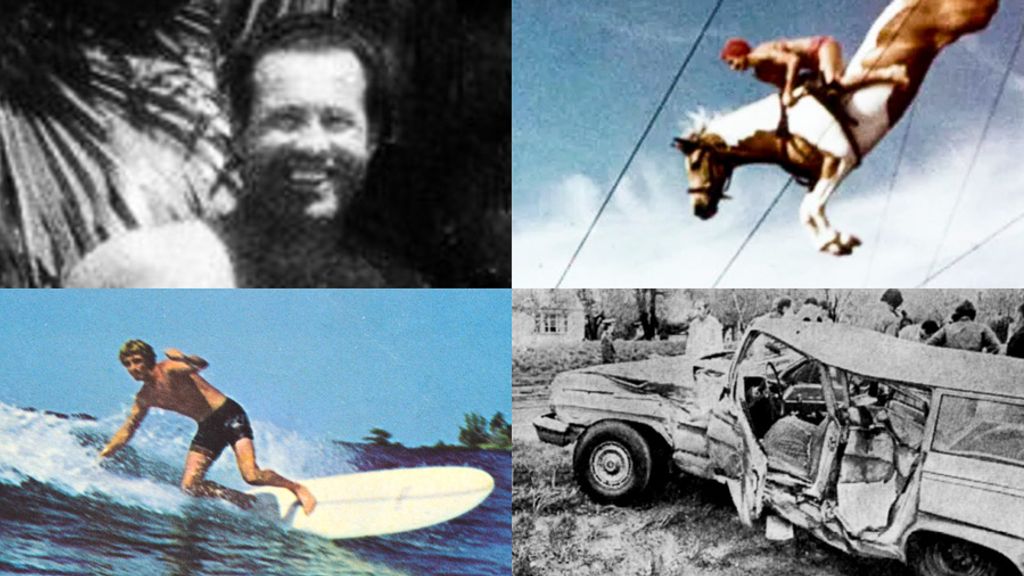

At some point in the 1950s, Gose moved to New Jersey and became a good enough surfer to place runner-up in the Senior Men’s division at the ’66 East Coast Championships. His contribution to surf media, however, wasn’t anything special. He got some nice water shots of Nat Young at the ’68 World Championships in Puerto Rico, and did some middling East Coast contest writeups that year and the next, but as far as I can tell he was off the surf beat by the early 1970s.

Which brings us to the exceptional bits of Gose’s life, all of which seemed to take place away from the lineup. He was an ex-Navy man who became an Atlantic City stunt performer. His wife, Barbara—17 when she met and married Gose; they had four kids together—was one of the only female Steel Pier horse divers. Barbara said Mickey was good-looking and fun to be around, but a heavy drinker, and I believe her. Apart from one grainy low-res shot of Mickey smiling for the camera, the only Gose-related picture I can find online shows his station wagon destroyed on the side of the highway. Gose, the photo caption reads, was hospitalized but in good condition. This was 1972. Barbara by that point had bailed out. “I needed to think about how I was going to make a living and raise my sons.’’

The hard-luck final verse in The Ballad of Mickey Gose will be conjured from a 1978 Philadelphia Inquirer article describing the rush to find and train card dealers for Atlantic City’s pending casino boom. Among the thousands of who showed up for an ad-hoc “dealer’s school” was Gose, described by the paper as “a barrel-chested bearded man in a gray turtleneck sweater and blue leisure suit . . . a sometime photographer and sometimes mechanic who is unemployed.”

The quote that follows, from Gose himself, wavers between funny and heartbreaking, and to my ears it is premium-grade country-western. “This [new career as a card dealer] is strictly money, strictly a job, and a future for my kids. When they get older, I’ll teach them how to deal cards.”

Gose died in 1985, at age 53, which reminds me that during his heyday days as a New Jersey surfer he drove a 1955 black Cadillac hearse with whitewalls, surfboard and some old blankets in back, along with, I’m guessing, at least a half-dozen empty bottles rattling around side to side.

The LP cover practically designs itself.

Thanks for reading, everyone, and see you next week.

Matt

[Nat Young surf pic by Mickey Gose]