SUNDAY JOINT, 5-7-2023: MIKE HYNSON IS YOUR VANDALIZING GUEST OF HONOR

Hey All,

Have a look at this somber little 1963 TV news clip of Mike Diffenderfer, Mike Hynson, and Bill Caster being interviewed about a just-announced project to create Tourmaline Surfing Park, in San Diego. The first breath of onshore wind has just come up, but the surf looks great. That's Pacific Beach Point in the background, and in my desultory two semesters at San Diego State, when I was driving back and forth on this wave-filled section of coast like it was my job—which it pretty much was; that’s how I pulled straight Cs—I never saw the Point looking as inviting as it does here. (Surfing Guide to Southern California, a 1963 book that was half Bible and half treasure map to surfers of my generation, said of PB Point: "Thick fat waves—we used to cheer if they broke. Better at low tide. Mainly right, occasionally lefts." Yeah, shine that, we drove right past on our way to Sunset Cliffs.)

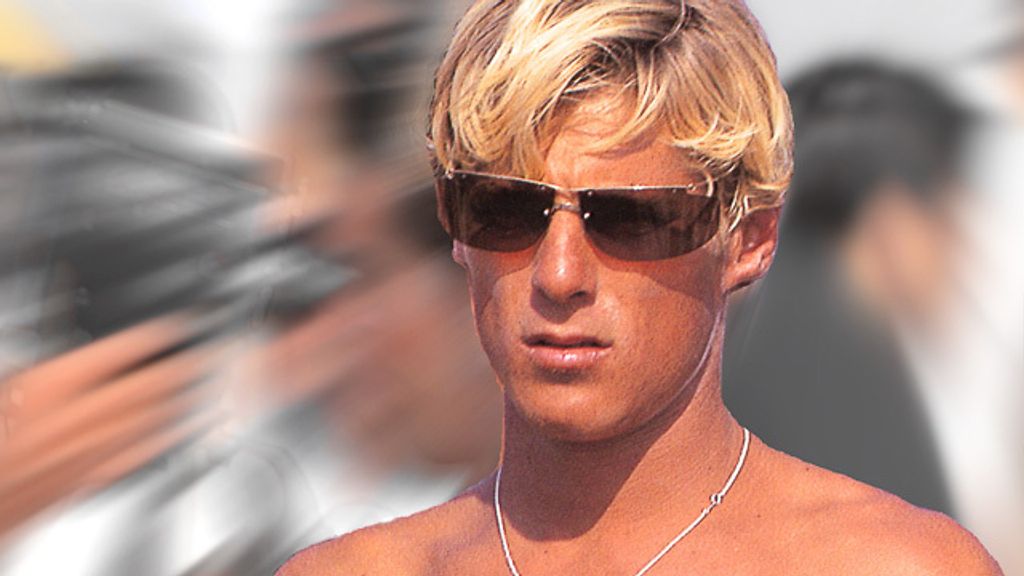

Even with those distant empty waves, though, you can’t take your eyes off soon-to-be Endless Summer star Mike Hynson.That gleaming-white fastback hair and and slightly put-upon squint, the three-quarter-sleeve cardigan, the casual parade-rest stance. Hynson is straight 101-proof confidence. Yet he confounds me, and always has. Hynson comes off as small and oversize at the same time. A leader and a hustler—somebody who, like Miki Dora, I might from a distance thrill to or be entertained by, but would go out of my way to avoid having contact with. Bruce Brown had a lifelong friendship with Endless Summer's other star, Robert August, but famously disliked and feuded with Hynson. Yet the bantamweight regularfooter, as writer Jamie Reno points out in this bittersweet San Diego magazine article feature, draws the camera as if he were magnetized: "Hynson’s charismatic style, in and out of the water, and his chiseled blond surfer-boy good looks are, along with Brown’s folksy narration, among [Endless Summer's] most identifiable aspects.

The Hynson story is long and cursive, and we will no doubt return at some point to talk about his contribution to board design (the hard-edged Hynson rail, as Gerry Lopez said, "changed tuberiding overnight"), and his involvement with the Brotherhood of Eternal Love ("the Hippie Mafia," according to Rolling Stone), and the cinematic trainwreck that was Rainbow Bridge ("a ludicrous farrago of pseudo-mystical acid babble," according to the kindest review I could find).

But for now, let's stay with Hynson's amazing little pas de deux with Tourmaline.

Keep in mind that this all takes place almost literally in Mike's backyard. He grew up in Pacific Beach and was a charter member of the Windansea Surf Club. The club was formed in part to reduce the friction that had developed between beachfront homeowners and the first wave of post-Gidget teenage surfers who were moving like jams-wearing tadpoles across the San Diego streets, beaches, and lineups. There were flashes of nudity as surfers changed. There was occasional day drinking, lots of swearing, some trespassing, and a bit of lightweight property destruction, mostly trampled yards. White suburban teen-level problems. "Rowdyism" was the term of choice. But the local press was filled with angry anti-surfer letters and slightly more reasonable but still scolding editorials. This was common at the time, in America and Australia, but credit to the more vocal anti-surfing San Diegans for going the extra rhetorical mile: "The devil is breaking loose on the beaches," one letter-writer said; "they [surfers] feel everything belongs to them, [so] they're playing the Communist role," another added, so right there we're up against God and democracy, both. In response, beachside city councils began to develop and in some cases deploy plans to limit or ban surfing. Incredibly, given their reputation, Windansea went to bat on surfing's behalf at various San Diego community centers and town halls and was able to knock back some of the harsher anti-surfing plans.

One plan that went through, however, was Tourmaline Surfing Park. It wasn't stated directly, but the point here was to corral the surfers onto an undeveloped stretch of beach that nobody really wanted, while the rest of the nearby beaches would either be off-limits or potentially off-limits, depending on how the surfers behaved going forward. And when I say nobody really wanted Tourmaline, that very much includes surfers, because it was a crap break, a non-break; in fact, it didn't even have a name at that point, you just walked over it to get to PB Point. Hynson and Diffenderfer and Caster all speak to this very idea, in the clip above. They signed and helped circulate a petition against the park.

So that's why Hynson looks so irritated in the video. That and the fact that, in his surf star prime, when he wasn't grinning like the kid who just threw a lit pack of firecrackers into the girls' bathroom, he had resting Tucker Carlson face.

Here's what happened next. The Tourmaline Surfing Park took over two years to build, mostly because the construction area—a new road down the canyon itself, opening onto a parking lot with bathrooms and outdoor showers—was regularly vandalized, and no prize to anyone for guessing who the chief vandal was. "I just kinda got into it," Hynson later said. "I'd hit it, pull some stuff up, leave. I remember jumping into a tractor and popping it in gear, the thing started rolling and I jumped off. I was gone by the time [it got to] wherever it ended up."

Tourmaline Surfing Park had a formal, city-sanctioned opening ceremony, with press and dignitaries and well-wishers, on Saturday, May 29th, 1965. Three-hundred surfers were kind of there, but not really. The Western Regional Surfing Championships were purposely scheduled that same weekend, but down the beach a ways, at Emerald Street, near Crystal Pier—because, again, Tourmaline was that close to not even being a surf break. Two related but separate events, in other words. Back at the ceremony, San Diego mayor Frank Curran declared the last seven days in May to be "Surfing Week."

On hand to cut the ribbon—and I wish I had a picture, because you know he was looking like a million bucks—was Mike Hynson.

As Marilyn Monroe said, If you're going to be two-faced, at least make one of them pretty.

Thanks for reading, and see you next week.

Matt

PS: The happy ending to the Tourmaline Surfing Park story is that with a lot of added sand trucked in from a San Diego River dredging project, plus some minor but effective coastal rearrangement by a huge series of winter storms in 1983, Tourmaline actually became a decent surfing wave and is now a beloved part of the local community, surfing and otherwise. This process was well underway by 1969, in fact, as you can see in this news clip.

PPS: A rock-and-marble Tourmaline Surfer's Memorial, located on the beach side of the parking lot and dedicated to the "fine men and women who have grown up within the Tourmaline culture, and carry the positive traits learned here into their lives," was unveiled in 2008. Hynson is among the honorees, of course—but the featured surfer is fellow PB local Skip Frye, the mellow and soft-spoken Yin to Hynson's bridge-burning Yang, which goes to show that the nice-guys-finish-last adage, unlike the memorial itself, is not cast in stone.

PPPS: 1930—that's San Diego River in the center, pre-jetty Ocean Beach to the south, Mission Beach and Pacific Beach to the north. Surfing, obviously, needs more un-messed-with rivermouths.

[Photo grid, clockwise from top left: detail from Rainbow Bridge poster; grab from 1963 CBS-8 Tourmaline Surfing Park news segment; Mike Diffenderfer, Windansea, 1969, photo by Glenn Fye; grab from '63 news segment; grab from 1969 Tourmaline news segment; Mike Hynson kick-stall, photo by Ron Stoner. Hynson portrait by Stoner. Hynson surf shot by Stoner. Before and after shots of Tourmaline Park (1965 after shot by Brad Barrett. Grinning Mike Hynson by Ron Church. Hynson at Rincon by Stoner. 1930 aerial photo of San Diego coastline.]