SUNDAY JOINT, 6-27-2021: ALOHA AND THANK YOU JOE QUIGG

Hey All,

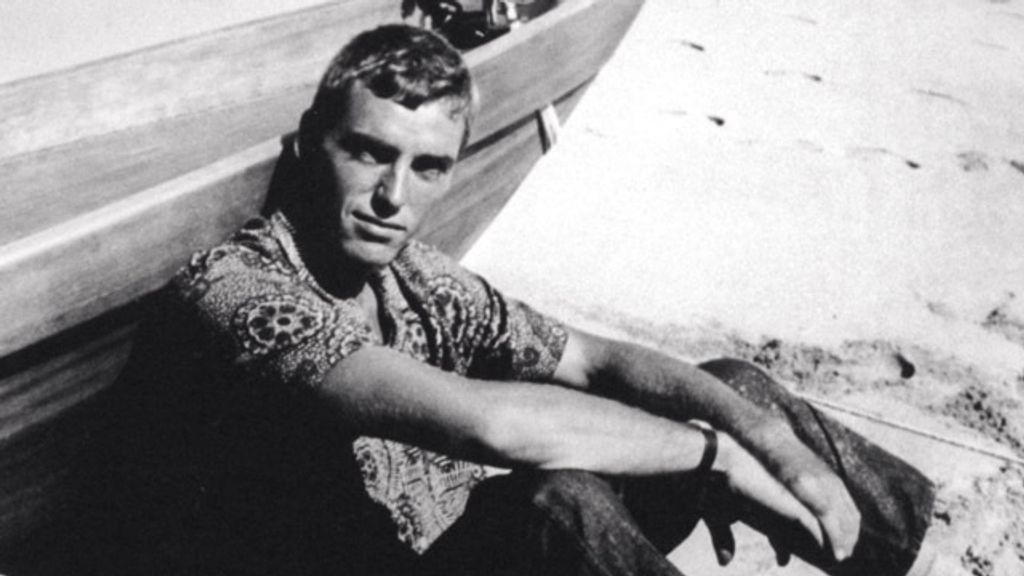

Joe Quigg, the Stradivarian-level midcentury boardmaker who more or less invented surfboard rocker—which gets us to the first cutback, which in turn gets us to John Florence at Haleiwa—and did it with great style and warmth, died last weekend, just a few days short of his 96th birthday.

Design-wise, Quigg is best known for a pair of boards he made in 1947: the Darrylin Board (small, light, rockered, easy to turn; the original “Malibu chip”); and the first modern pintail, built specifically to deliver Joe from Indicator Rincon all the way to Highway One, and Mission Accomplished the first day he took his new board out there.

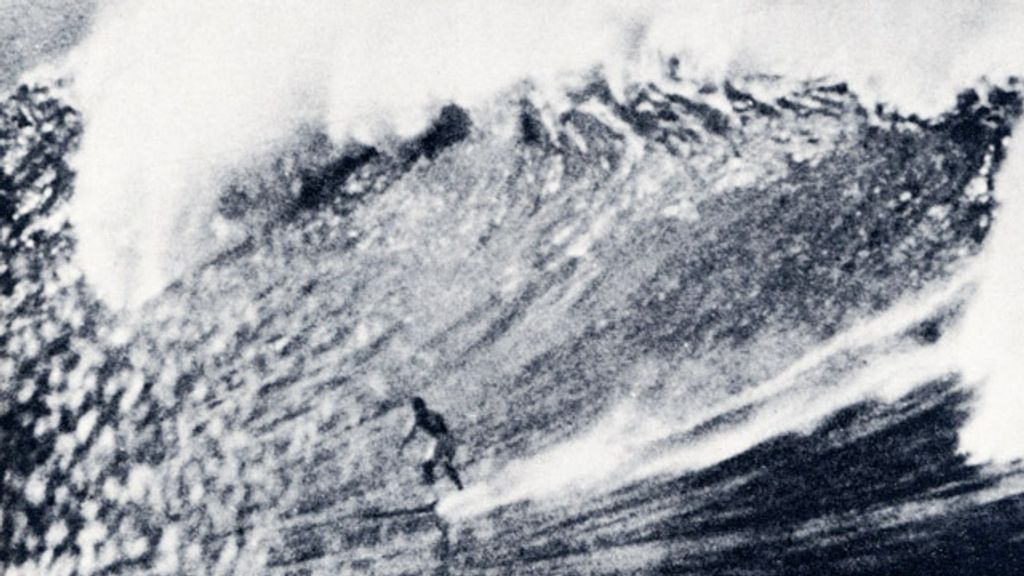

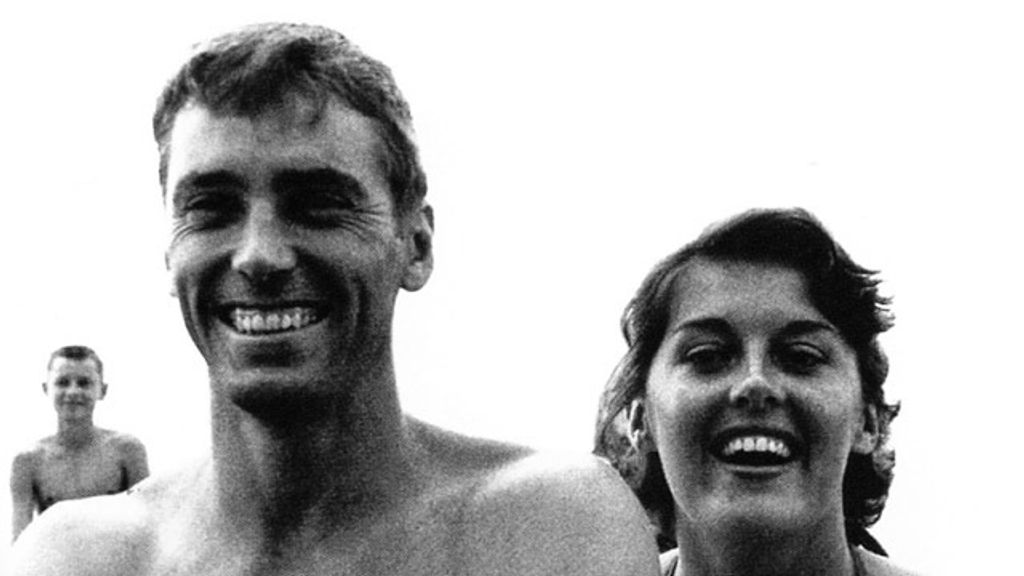

The fifth pintail Quigg built (date unclear, but 1951 is a good guess) he described as “all-balsa modern shape with rocker, low rails, about 9' 6" and very light—at least half the weight of other boards.” Jim Fisher of San Francisco rode it on a huge day at Makaha (below); a few months later, on the beach at Malibu, Gard Chapin handed Quigg $50 to buy the same board for his delinquent high school son Mickey, who at that point was more Chapin than Dora and becoming more cat-like by the month (below).

This whole past week was spent hip-deep in the Quigg files, and while my appreciation for the man and his work has only grown, the timeline for his most fertile design period (1947 to 1954, more or less) remains stubbornly compressed and complicated, as do the dynamics between the key players. That said, Quigg himself brings so much snap and jazz to the narrative, and the period itself feels both relaxed and spring-loaded, so the deep-dive I’ve lined up here should be worth your time.

QUIGG INTERVIEW BY STEVE PEZMAN

“DARRYLIN, OH DARRYLIN,” QUIGG IN “HISTORY OF SURFING”

In “History,” I champion Quigg’s boards as the beginning of performance surfing as we know it today, and we’ll get back to that in a moment. But as much as I appreciate what Quigg produced, I am just as grateful for the way he went about it: “The Malibu chip was, first and foremost, a better-riding board. But it was also a touchstone for a group of surfers who helped to change the sport’s disposition. In the hands of people like George Freeth, Tom Blake, Bob Simmons, and even Pete Peterson, surfing at times looked to be the province of loners and misfits. This wasn’t necessarily a bad thing, and they helped give the still-new sport its own particular energy and independence. But Joe Quigg and the rest of the Malibu chip innovators were closer in spirit to Duke Kahanamoku. They smiled their way through the whole process, from designing boards to wave-riding. They were sociable. They opened things up to girls and beginners, and managed the difficult trick—rarely achieved in decades to come—of presenting the sport as both cool and friendly.”

Yet what struck me this week, again and again, was the degree to which Quigg, decades later, was still struggling with his not-always-friendly feelings about fellow postwar boardmaker Bob Simmons. Bob, of course, received, and continues to receive, way more credit than Joe for creating the modern surfboard. Simmons, not Quigg, was a first-round pick in the 1966 International Surfing Hall of Fame. Simmons, not Quigg, got his own chapter in History of Surfing.

I blame Joe for not being a Cal Tech math wizard, like Simmons, who could cut loose with a spellbinding line of hydrodynamic bullshit. (Quigg, on the other hand, shrugged and called himself a “trial and error man.”)

I blame Joe for being friends with Tommy Zahn and Matt Kivlin who, like Joe, were handsome and friendly boardmakers. Quigg is remembered as being part of a trio. Simmons is the lone genius.

But mostly I blame Joe for not dying young, while surfing, like Simmons.

No wonder we first pay attention and tribute to Simmons and then get around to Quigg.

Still, some of the comments Joe made about Bob in the interviews above, to my ears, sound more personal than that, and I idly wondered what the relationship between the two was really like (Joe and Bob worked together, and Quigg is on record somewhere as saying he loved and respected Simmons), and where the stress points were—apart from the fact that Simmons sat Quigg down for some marathon nighttime design-theory talks that devolved into yelling matches.

Yesterday I came across a passage by Dave Rochlen, something I’d never before read, in a 1963 Surf Guide article about Malibu. I’ll quote at length, because the story is both funny and dark and, as far as what I’m talking about here re Quigg and Simmons, revealing. I’ve edited it just a bit.

Simmons was a rare, rare man. Here was a guy who believed pretty radically in what he believed in. He had a certain kind of integrity. His behavior never changed. You always asked yourself, What were the conditions under which he would change? What would happen if this guy was out in front of an approaching freight train. Would he change?

Simmons originally built boards to trim and just GO. And this occasionally gave him trouble. He once ran me down when I was going tandem—just ran right over us. Another day he ran Quigg down two times in a row. Quigg swam over and pulled Simmons off and ducked him and held him under till he almost drowned. If you got Bob Simmons down and pounded his face into the sand and tried to drown him, as I saw Joe Quigg do once, twice, three times, it just didn’t matter. Quigg would say, “Are you going to do that to me again?” And Simmons would come up and spit in his face.

So, yes, it was personal between Joe and Bob, as well as professional. Very much so.

There is so much more to the Quigg story than his deal with Simmons, but it kind of obsessed Joe, and it came up again and again while reading through all the Quigg material this week. Apologies if this Joint leans more Simmons than it should.

On the other hand, why stop now? I’ll finish by saying there is no Cult of Quigg, the way there is for Simmons, because there is no need. Collectively, we began riding Joe’s boards in 1950, or thereabouts—and never stopped.

Thanks for reading, and see you next week.

Matt

[Photos: Joe Quigg, Tom Zahn]