San Onofre

Relaxed, tradition-soaked Southern California surf break located at the north end of San Diego County, adjacent to San Clemente; home to the Pacific Coast Surf Riding Championships from 1938 to 1941; regarded since the end of World War II as a friendly surfing sanctuary for families, beginning surfers, and old-timers.

Origins for the name "San Onofre" are unclear, but the area may have been named after the desert-dwelling hermit Saint Onuphrius. California goofyfooter Bob Sides, driving through what was then part of the Rancho Santa Margarita in 1933, noticed good waves across the tracks and down the dirt cliffs from the San Onofre train station; Sides quickly convinced Lorrin "Whitey" Harrison and a few others at Newport Beach's Corona del Mar jetty—a favorite break for early generation California surfers— to make a two-day San Onofre surf exploration.

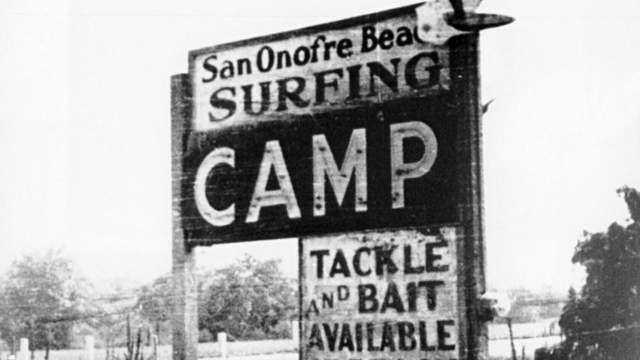

After a jetty extension shut down the waves at Corona del Mar in 1935, San Onofre became one of California's most popular surf breaks; "a meeting place," as longtime San Onofre regular Dorian Paskowitz later recalled, "for surfers from San Diego's Tijuana Sloughs to Steamer Lane in Santa Cruz." Weekend camp-outs, Paskowitz continued, were filled with "Hawaiian guitar, Tahitian dancing and no small amount of boozing."

Every notable surfer in California from the mid-'30s to the early '40s visited San Onofre, including Tom Blake, Cliff Tucker, Tulie Clark, Gard Chapin, Doc Ball, and Hoppy Swarts. Santa Monica's Pete Peterson, the era's best surfer, won two of his four Pacific Coast Surf Riding Championships at San Onofre, in 1938 and 1941.

After World War II, with the development of shorter, lighter surfboards, performance-minded California riders began looking for more challenging waves at places like Malibu and Windansea. San Onofre, along with hundreds of square miles of inland property, had meanwhile been turned over to the U.S. Marines; when it looked as if the Marines would shut San Onofre down to surfers, Orange County surfer-dentist Barney Wilkes led the drive in 1952 to establish the San Onofre Surfing Club, whose members were allowed beach access.

By the early '60s, San Onofre was enshrined as a warm, nostalgic, easygoing family-style surf break. Club members were singularly devoted to their beach. "This is our life," as one put it in 1961. "All the days in-between are bare existence." A palm-frond shack in front of the main surf break became a surf-world icon, as did the yearly San Onofre Surf Club car window sticker. By 1965 there were 800 club members, including Los Angeles Times publisher Otis Chandler and Gunsmoke star James Arness, and another 500 on the waiting list.

In 1973 San Onofre became part of the California State Parks system, and was opened to the public. Five years earlier the break lost a measure of its wilderness cachet with the opening of the looming twin-reactor San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station, but otherwise the Marine-operated area remained almost completely undeveloped. A leak in early 2012 released a small amount of radioactive steam, forced the nuclear plant to close, and in mid-2013 it was announced that the plant would be closed and dismantled. But as environmental advocate Bart Ziegler noted in a 2021 Voice of OC article, "3.6 million pounds of [nuclear waste], will be left behind, stranded in a storage vault that straddles a seismic fault system. No one knows how long the spent fuel will remain in its location 100 feet from the sea," and there were no "independent, real-time air-quality monitoring" structures in place.

While San Onofre State Park stretches along nearly two miles of wave-filled beachfront, there are two main breaks, both located in the northern half of the park: Old Man's (also called Outside), the traditional San Onofre break and onetime home to the Pacific Coast Surf Riding Championships, features a broad, generous, multitiered wave field, similar to that of Waikiki. Small rocks fill the shoreline, and the break is often crowded with longboard-riding novices, but the surf is otherwise easy-breaking and hazard-free. Waves at the Point, located a quarter-mile north of Old Man's, break closer to the beach and are steeper, smaller, and marginally harder-breaking. Old Man's and the Point are ridden almost exclusively by longboarders; shortboard surfers ride further to the north at Church, Trestles, and Cottons. Dogpatch and Trails are both located just to the south of Old Man's and offer similar easy-breaking waves.

The 1977 United States Surfing Championships were held at San Onofre; hundreds of regional, national, and international longboard contests have been held here since the mid-'80s, including the Hobie San Onofre Classic and the Roxy Wahine Classic. Since the mid-'00s, San Onofre has been one of the sport's most popular SUP breaks.

The prewar San Onofre surfing scene is featured in Doc Ball's seminal 1946 photo book California Surfriders, and in Surfing San Onofre to Point Dume: 1936 —1942, a collection of Don James photos. Whitey Harrison and Dorian Paskowitz were among the still-active senior San Onofre surfers featured in "Endless Summer," a 1990 Life magazine feature. "The cosmic forces of San Onofre made me," Paskowitz told Life. "In these waves I found a power that took a nice Jewish boy and made him a nobleman." Surfer's Mecca: San Onofre, a documentary, was released in 1997. San Onofre: Memories of a Legendary Surfing Beach, the biggest surf book ever published at 1,500-plus pages, came out in 2020.

The San Onofre Foundation, a nonprofit environmental preservation group, was founded in 2008.

San Onofre, early '50sSubscribe to view

San Onofre, 1963Subscribe to view

Don James (left) and friends, San Onofre, 1939Subscribe to view

Cori Schumacher, San Onofre, 1998.Subscribe to view

San Onofre, 1963. Photo: LeRoy GrannisSubscribe to view

San Onofre, early 1940sSubscribe to view

San Onofre, early '50s

San Onofre, 1963

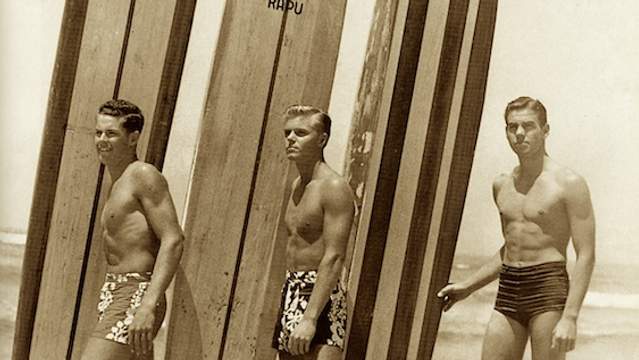

Don James (left) and friends, San Onofre, 1939

Cori Schumacher, San Onofre, 1998.

San Onofre, 1963. Photo: LeRoy Grannis

San Onofre, early 1940s