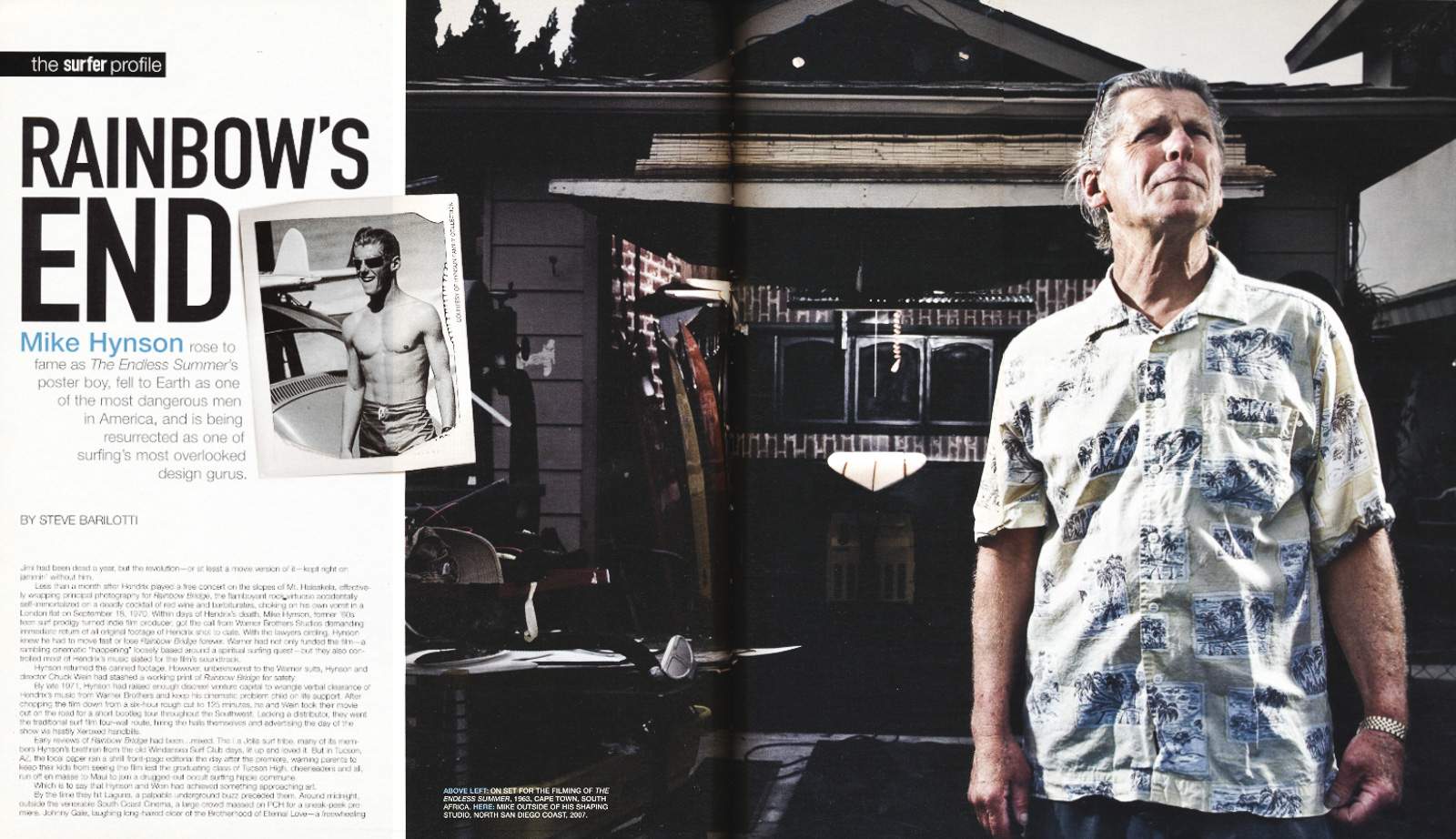

“RAINBOW'S END,” MIKE HYNSON PROFILE BY STEVE BARILOTTI (2007)

Steve Barilotti's profile on Mike Hynson ran in the August 2007 issue of SURFER. This version has been slightly edited.

* * *

Jimi Hendrix had been dead a year, but the revolution—or at least a movie version of it—kept right on jammin’ without him.

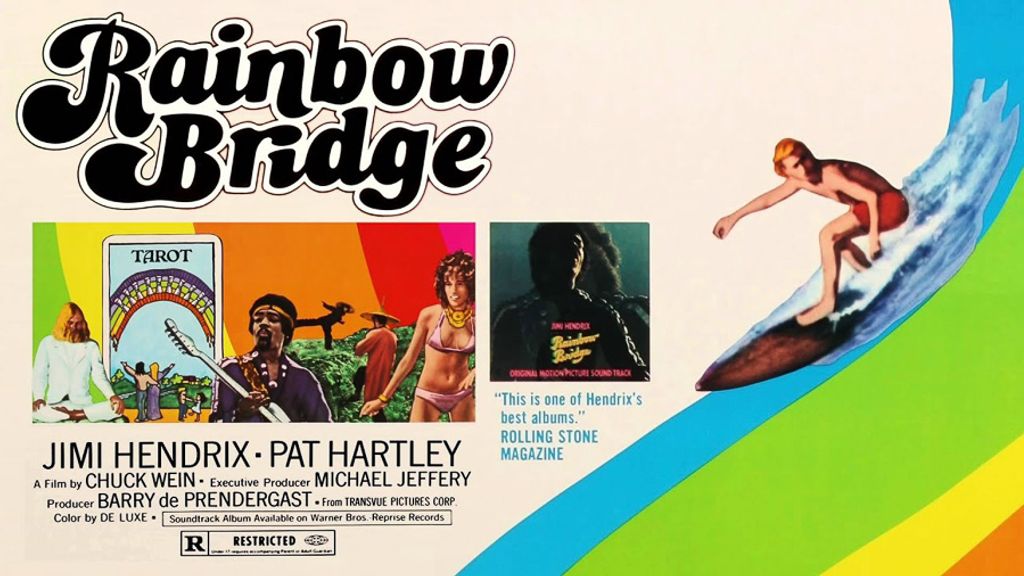

Less than a month after Hendrix played a free concert on the slopes of Mt. Haleakalā, effectively wrapping principal photography for Rainbow Bridge, the flamboyant rock virtuoso accidentally self-immortalized on a deadly cocktail of red wine and barbiturates, choking on his own vomit in a London flat on September 18, 1970. Within days of Hendrix’s death, Mike Hynson, former ’60s teen surf prodigy turned indie film producer, got a call from Warner Brothers Studios demanding immediate return of all original footage of Hendrix shot to date. With the lawyers circling, Hynson knew he had to move fast or lose Rainbow Bridge forever. Warner had not only funded the film—a rambling cinematic “happening” loosely based around a spiritual surfing quest—but they also controlled most of Hendrix’s music slated for the film’s soundtrack.

Hynson returned the canned footage. However, unbeknownst to the Warner suits, Hynson and director Chuck Wein had stashed a working print of Rainbow Bridge for safety.

By late 1971, Hynson had raised enough discreet venture capital to wrangle verbal clearance of Hendrix’s music from Warner Brothers and keep his cinematic problem child on life support. After chopping the film down from a six-hour rough cut to 125 minutes, he and Wein took their movie on the road for a short bootleg tour throughout the Southwest. Lacking a distributor, they went the traditional surf film four-wall route, hiring the halls themselves and advertising the day of the show via hastily xeroxed handbills.

Early reviews of Rainbow Bridge were . . . mixed. The La Jolla surf tribe, many of its members Hynson’s brethren from the old Windansea Surf Club days, lit up and loved it. But in Tucson, Arizona, the local paper ran a shrill frontpage editorial the day after the premiere, warning parents to keep their kids from seeing the film lest the graduating class of Tucson High, cheerleaders and all, run off en masse to Maui to join a drugged-out occult surfing hippie commune.

Which is to say that Hynson and Wein had achieved something approaching art.

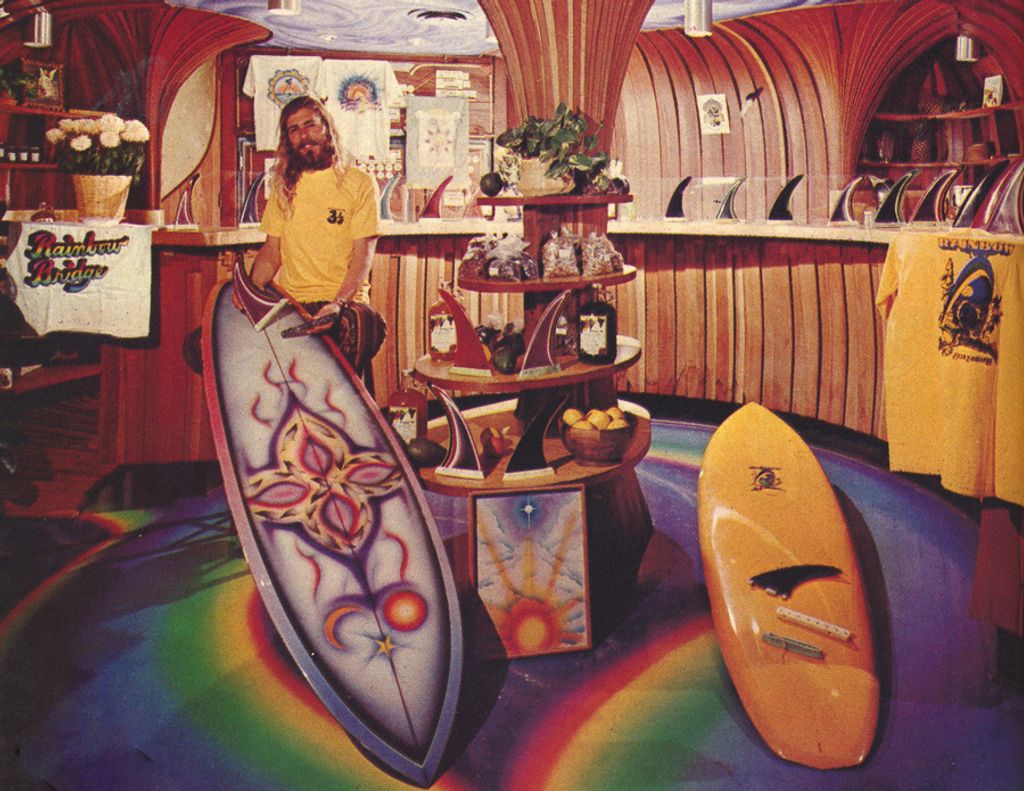

By the time they hit Laguna, an underground buzz preceded them. Around midnight, outside the venerable South Coast Cinema, a large crowd massed on Pacific Coast Highway for a sneak-peek premiere. Johnny Gale, laughing long-haired elder of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love—a freewheeling crew of spiritual seekers and psychedelic buccaneers—was thoroughly enjoying his birthday party, handpicking the audience at the door to make sure only the most righteous dudes and prettiest girls came through. Several ornate airbrushed surf boards, all shaped by Mike Hynson, were displayed in the lobby like geodesic trophy kills. These boards—thick pintails with severe downrails from nose to tail—were stars in their own right, having been featured throughout the film’s surfing sequences.

The Rainbow Bridge premiere was Hynson’s present to Gale, a spiritual fellow traveler and brother surfer. The son of a well-to-do Newport marine engineer, the diminutive Gale was a charismatic and flamboyant LSD baron, known to chum the crowd at rock concerts by flinging handfulls of Orange Sunshine tabs—the Brotherhood’s premier acid—like dragon seeds to the cheering throngs. Within a few short years, Gale had amassed a fortune through illegal drug sales. Hynson, who bore a passing resemblance to the blond, shoulder-tressed Gale, had connected with him years earlier, and by 1969 they’d gone into business together as Rainbow Surfboards in Laguna Beach.

Sprinkled throughout the milling crowd were several federal drug enforcement agents, some in hippie camouflage. Likely among them was Neil Purcell, a young Laguna Beach police officer who was looking to make his career by bringing down the Brotherhood. The agents took notes and methodically built their case against Gale and his drug-running agents, who thus far had outfoxed authorities at nearly every turn. This included Hynson, age 28, who had been associated with the Brotherhood since its arrival in Laguna in the mid-’60s.

The Brotherhood, set up as a church in 1966, proclaimed LSD and other mind-altering drugs to be sacramental pathways to enlightenment. Their philosophies drew heavily on the preachings of psychedelic high priest Timothy Leary, who at times lived with Brotherhood members in Laguna. After Leary's 1970 conviction from a 1968 marijuana bust by Purcell, then-President Richard Nixon declared Leary “the most dangerous man in America” for corrupting the minds and morals of the nation’s youth.

Nixon allegedly had Hynson on his enemies list as well. Certainly Hynson was much cooler, sexier, and more accessible to the young than Leary, and as early as 1964 had already popularized his subversive, anti-authoritarian slouch through the now-iconic Endless Summer poster.

With the lawyers circling, Hynson knew he had to move fast or lose Rainbow Bridge forever.

* * *

There was a time when Michael Lear Hynson was heir apparent to all that was cool and commercial in the surfing cosmology. A SoCal golden child with slick-backed blond hair, Ray-Bans, and a seamless style copied from the Phil Edwards’s playbook, Hynson was an airtight package that could be readily sold to the mushrooming mid-’60s surf population and beyond. After Endless Summer broke big-time in 1966, Hynson’s look, now seen in full-page ads in SURFER and Surfing Illustrated, was copped shamelessly by mainstream media as the archetype of California style.

Back at the theater, through a thick fog of DMT-laced marijuana smoke, the lights dimmed and the film began.

Rainbow Bridge, the audience soon discovered, lacks a traditional three-act arc, or even a script. The main action is following foxy, Afro-adorned Pat Hartley, one of Andy Warhol's Factory Superstars, as she navigates a metaphysical rabbit’s hole from the Sunset Strip to a commune of eclectic young seekers on Maui. About 15 minutes into the film, however, it cuts abruptly to David Nuuhiwa, then considered a leading avatar of the shortboard revolution, dropping in switchstance down a zippering blue Maalaea wall. Nuuhiwa’s surfing was as ingenious as it was smooth, with reverse takeoffs, go-behinds, tail slides—all performed with the kind of mastery and flair that channeled Hendrix’s electrifying guitar licks.

Backing Nuuhiwa up throughout the film’s surf sessions is an all-star crew of surfers that included Gerry Lopez, Reno Abellira, Herbie Fletcher, and Barry Kanaiaupuni. They are shown tearing up an array of Maui summer breaks on Hynson’s radical new downrailers.

As the music crescendos up and out, the scene shifts abruptly to a tapestry-lined bedroom strewn with Oriental carpets, surf mags, Buddhas, incense burners, and three strategically placed high-aspect fins. Hynson and his surf buddy Les Potts are hanging out, chilling between swells. Behind them, a large poster of a shifty-eyed Nixon grins down malevolently. It reads, “Would you buy a used car from this man?”

An unidentified bearded Brother we’ll call Allan enters. Hynson and Potts are stoked to see him. Allan, hyper and garrulous, has just flown in from overseas and breathlessly reounts how he’d been detained by Honolulu customs officers, but finally, inexplicably, let go.

Allan then hands Hynson a carpet knife and tells him to cut open a panel on the board's bottom. Allan peels back the glass, digs down, and pulls out a large plastic bag filled with what looks to be rich brown potting soil. Hashish. Hynson and Potts make approving sounds. They spread the booty carefully over the board’s polished underside while Allan savors a pinch:

Allan: “Afghanistan . . . primo pollen . . . look at that."

Cut to a smoke-filled room and Hynson wearing a blissful, felonious smile, with Allan offering a toke to Tricky Dick.

This scene, which brought howls of derisive laughter from the audience, was an audacious slap in the face on Nixon, the DEA, and especially Neil Purcell. It was a bold, foolhardy act of defiance that spurred retaliation and a global manhunt that lasted more than 25 years.

Their tails tweaked once again—this time in their own backyard—the drug cops vowed to settle accounts once and for all. In the eyes of the law, the Brotherhood had crossed the line from rebellious doper kids dealing baggies of Mexican dirt-weed to professional criminals running a multi-million-dollar international smuggling fraternity Rolling Stone later dubbed “The Hippie Mafia.” What had been a droll fox-and-hounds farce suddenly turned deadly serious. Federal indictments were handed down within months, and some of the Brothers, if convicted, were looking at 20-year prison terms.

By mid-1972 the authorities had stepped up arrests and issued wanted posters featuring 26 Brotherhood members who had gone into hiding, including Johnny Gale. Leary exiled himself to Switzerland after escaping from a California prison with help from the infamous Weathermen, who had been paid $50,000 by the Brotherhood to spring their spiritual leader.

Not long after the Laguna premiere of Rainbow Bridge, drug agents raided Rainbow Surfboards’ storeroom. Several beautiful new boards, painstakingly airbrushed by local artists John Breden and Starman, were rifle-butted, Untouchables-style, before Hynson could convince the frenzied agents that polystyrene foam was the only thing stashed inside the fiberglass.

They left empty-handed, but with a warning: “We’re gonna get your fucking ass, Hynson. You and your band of goddamn drug-smuggling motherfuckers.”

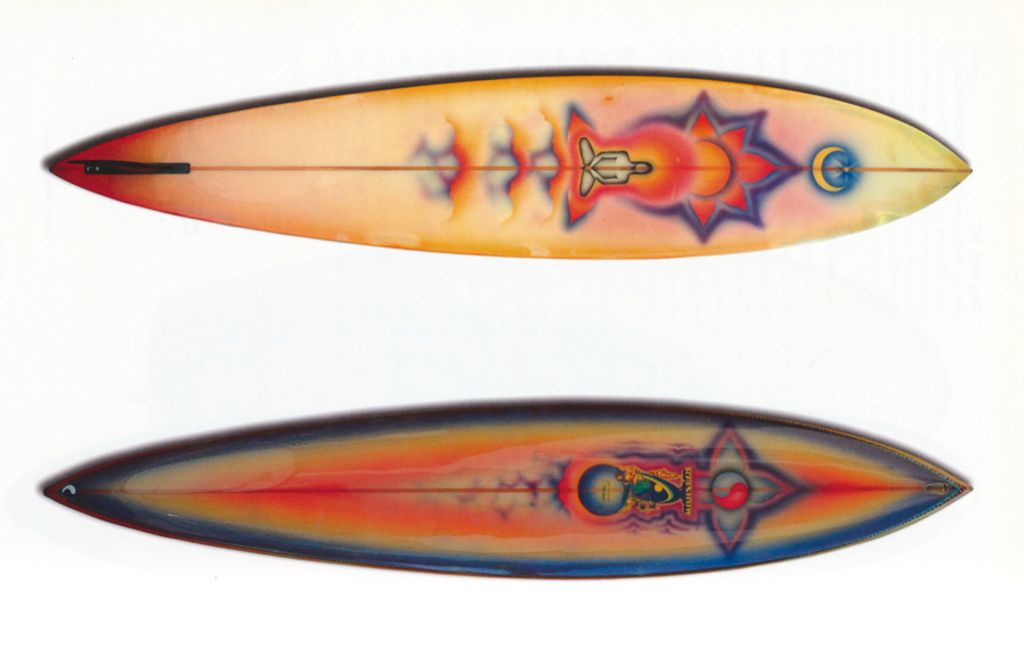

But the drug agents, not being surfers, had missed the cosmic plot—or joke—by 35 degrees. Never mind that the Brotherhood no longer used surfboards as drug mules or that the “hash” pulled out of Hynson’s board was actually Hershey’s cocoa powder. The real mind-altering substance contained in Hynson’s boards was in plain sight all along. Encrypted along those extreme nose-to-tail downrails was the password that allowed Gerry Lopez and others the means to explore Pipeline’s unseen realms.

Regardless, for Hynson, the Endless Summer and the Summer of Love were long over. The mother wave of all bad karma was feathering on the horizon, and the best Hynson could do for the next 25 years was pull in a deep breath and head for the bottom.

* * *

Of course, Hynson admits with a wily chuckle, he never said there wasn’t any contraband glassed in his boards. In fact, he found that the knowing wink of a psychotropic golden ticket made good marketing in those hazy days. And Hynson, schooled in the artful caper by masters such as Miki Dora, loved stirring a bit of curry into the pot.

“I used to really be good at spreading rumors,” recalls Hynson. “You know, you just tell the right person, and by the afternoon it was ‘Every Rainbow board’s got a stash in it!”’

Hynson leans back in front of a new laptop and contemplates his next move: electronic solitaire. It came bundled with spreadsheets and a basic video-editing suite, but outside of video games and a laboriously pecked e-mail, he has yet to figure out this latest tool’s place in the shop. He got it, ostensibly, to keep him dialed into online marketing at the Hynson website and to help write his memoirs, Transcendental Memories of a Surf Rebel. But Hynson, who by age 17 was a gifted production shaper, was trained to translate his idea through wood planes and calipers, not keyboard commands. If he wants to design something—a new tail design or his latest shaping “studio”—he just sketches it out on the back of an envelope with a carpenter’s pencil.

He clicks the mouse. Five of hearts over the six of spades.

The dude abides. At 64, despite years spent prowling the back alleys of up-market Southern California beach towns as a self-avowed “garage dweller,” Hynson still has that quizzical Eastwood squint mixed with a winning wise-guy smirk made famous over four decades ago with the first release of Endless Summer. Admittedly, the sun, drugs, and several stretches in county jail as a turnstile petty offender have etched their toll in his face. But when Hynson laughs, which is often and mostly for his own benefit, the worn aristocratic mask crumbles and he becomes the cocksure 21-year-old rake locked in perfect trim across the mythical perfect wave at Cape St. Francis.

Earlier, Hynson had taken me through the whole backstory of how he, Robert August, and filmmaker Bruce Brown had discovered Cape St. Francis—the film’s defining moment—almost by accident after an all-night drive. Peering red-eyed from his thatched holiday rondavel at daybreak, Hynson spied an apparition: a pristine, sand-bottomed right resembling a deserted Malibu, peeling head-high and seemingly forever. At first Brown and August were reluctant to walk up the point as they hadn’t seen the sets Hynson had. So Hynson flipped them the bird and struck out alone.

A half-hour later he caught his first wave, and the rest is history.

As he tells the story, I see him transported back over the decades—he’s standing on the dunes, feeling a brisk offshore ruffling the little hairs on the back of his neck.

“The feeling lasted forever. I mean, you talk about getting addicted or having a rush. Drove me crazy. ’Cause after that, you’ll do whatever it takes to get your adrenaline to go off like that again. It was like when the Navajo circle rugs together to create a spirit hole for good dreams to go, you know? I felt that we’d really done something. It created the whole perfect wave for the trip—and for the world.”

* * *

In the age of the venerated surfer-shaper, Hynson proved himself as creative as he was technically skilled. In 1965, using design principles learned from watching Phil Edwards shape at Hobie Surfboards, Hynson came up with his popular “Red Fin” signature model for Gordon & Smith Surfboards in San Diego. The Red Fin got its name from its distinctive broad red cutaway fin, another Hynson-designed feature. Narrow and temperamental, the Red Fin was a connoisseur’s ride, built for milking the most speed out of California point waves.

“Hynson was always playing with the rails,” says Skip Frye, Hynson’s high school surf buddy and later fellow G&S shaping stablemate. “Rails were the primary thing in the '60s. I mean, back then there wasn’t much to a board. You had a plane shape but no V-bottom or anything like that. So the rails were super important to a board’s performance. Hynson won’t cop to it now, ’cause he hates those soft 50-50 rails, but his rails, even in that period, were really good. Probably a lot of my rail today comes from him.”

Not long after the Red Fin came out, Hynson quickly assembled a team A-list surfers that included Frye, Billy Hamilton, Butch Van Artsdalen, Barry Kanaiaupuni, and Herbie Fletcher. They would travel the California coast together with SURFER staff photographer Ron Stoner, often dominating a spot so ruthlessly that they became known as the “Red Fin Mafia.” Stoner’s shots from a November 1966 Red Fin day at the Ranch include a photo of Frye locked in on the nose, perfect parallel-stance trim, while Hynson, knee-paddling in the foreground, looks on. The shot became an icon of the period.

Within two years, however, Red Fins boards had become relics gathering dust on the showroom racks. Hynson, already ahead of the curve after having a preview of the shortboard designs McTavish and Greenough were building in Australia in 1967, had begun cutting down his boards to fit not on but in the wave. He needed increased wave-speed and power to test his new boards, and Hawaii, just a six-hour flight away, could provide it.

Hynson was no stranger to Hawaii, or Pipeline. A Navy brat, he'd shuttled between Oahu and the mainland as a young boy before settling down in San Diego’s Pacific Beach. By his late teens, Hynson was one of the promising juniors spending his winters bunking up on the North Shore, tackling Sunset and Haleiwa and even the rare day at Waimea. Pipeline was considered suicide.

In 1961, however, minutes after Phil Edwards paddled back out from surviving the drop and slot from what is arguably the first completed standup ride at big Pipe, Hynson paddled out. He took off on a set wave that topped Edwards’s by at least two feet. As the footage from Bruce Brown's Surfing Hollow Days showed, Hynson got to his feet OK, but as the wave jacked, the nose on his rocker-free plank caught, and Mike first augered into the trough then was lifted back up for an appalling over-the-falls wipeout.

Hynson shook it off and salvaged his dignity by carefully navigating his way through on a subsequent smaller wave, but he had learned the hard way that the current boards were unsuitable for Pipeline’s fast-pitching tubes. His mind knew what needed to happen, but his equipment was a study in compensation at best. It took eight seasons and a healthy dose of psychedelics to eventually parse out what was needed to ride Pipeline as an art form.

By 1969, a few prototype downrail boards had already turned up—Vinnie Bryant and Bunker Spreckels were on point—but they were considered as eccentric as their inventors. Shaping guru Dick Brewer, who had led the American shortboard charge under his own label beginning in the spring of 1967, had incorporated the downrail into the tail of a few boards, with limited success. Hynson, however, had seen the downrail’s potential and began shaping his own, more radical versions. Hynson’s rails were ludicrously severe, mimicking the edge of a steam iron in profile and running the length of the board, nose to tail.

“At that point, rail-wise, It was really a competition between Brewer and Hynson,” says Fletcher, Hynson’s one-time North Shore neighbor. “I worked with Mike in the shaping room and we created a lot of things. We’d take acid and hang out all day listening to The Doors and The Stones, and then surf Backdoor. We’d share boards and watch each other ’cause nobody was there. Afterwards we’d compare notes and go back in the shaping room. It was a radical time. Everybody, the surfers and the shapers, was pushing it."

What Hynson and Fletcher soon discovered was that the low downrails, while limiting maneuverability, increased the planing surface and, hence, the speed. But, more importantly, a sharp edge gave the rider increased bite and control, allowing surfers to track through the spinning wall of a huge barrel with more confidence and control.

Gerry Lopez, along with Reno Abellira, was one of the first to receive Hynson's latest brainchild. The results were mind-boggling, what shaper and board pundit Dave Parmenter later called "the Continental Divide in surfboard development.’’

“Everybody wanted to ride in the tube, but the boards didn't allow it," recalls Lopez, who built his Pipeline career on boards incorporating Hynson’s rail design. “Before the late ’60s, the whole concept of ‘edge’ didn’t even exist, [Hynson’s] downrails were pretty extreme, but once we moderated them a bit, that was the big break. The boards really started to work after that. It changed tuberiding overnight and riding deep inside the tube at Pipeline became a real possibility. And that was all Hynson.”

Hynson, who by now had left G&S and was shaping under his own Rainbow Surfboards label, was meanwhile on a mission to change surfing through cosmically attained design. By 1970, Hynson was known as “The Maharishi," a bona fide celebrity surfer who dressed like a rock star and had entree to the '60s counterculture elite, a rarified circle with ties to Jimi Hendrix and Andy Warhol.

Hynson’s wife, Melinda Merryweather, a U.S. senator’s daughter and fashion model, introduced him to circles outside the insular surf world. It was her cheery grace and astute social acumen, in fact, that opened the door for Rainbow Bridge, and she proved a capable foil for channeling Hynson’s many fancies. In 1973, they opened a one-of-a-kind juice bar/fashion boutique/surf shop in La Jolla.

Hynson also began developing some of the first removable foiled fins with fin-savant Curtis Hesselgrave. To get the proper foil for a dolphin-inspired fin, dubbed the “Hy-Dol-Fin,” Hynson and a friend sweet-talked their way around the Sea World front office to have one of the handlers coax a trained dolphin named Cindy up on the ramp so that Hynson could meticulously trace and duplicate her dorsal fin. He wrote later, “The softness, the rounded corners, the fact that it’s a natural design that works for one of God’s perfectly functional creations. And if you can put your head in that place, and maybe this fin will help, it will be the beginning of a new awareness in surfing.”

“There were no fins at the time with that unique configuration,” states Hesselgrave, who went on to design fins with the world’s leading manufacturers, including Fins Unlimited and Future Fins. “Mike’s intuitive strength as a designer was that he was always able to gather diverse elements and make them hang together so they worked as a whole. That's an extremely rare quality.”

Hynson’s guru act, however, didn’t go over well with the jock-ocracy of organized competitive surfing looking to make their fortunes in the sport. As a mute poster silhouette, Hynson was a perfect marketing icon. As a high priest of surfing psychedelia, he was derided and marginalized. Hynson could be cocky, abrasive, and often spouted a muddled spiritualism that alienated the reigning old guard. His choice to go it alone, without the backing of a leading brand such as Hobie or G&S, resulted in his being subtly moved out of the golden light of surf-media celebrity and assigned the status of drug-addled eccentric.

Which wasn't entirely wrong.

As the '70s wore on and cocaine entered the scene, Hynson descended into a downward spiral of drugs, excess, and debt scripted right out of a VH1 “Behind the Music” episode. Several unsuccessful rehab cycles followed.

A heavy coke habit eventually stripped away the zen visionary and playfully mischievous surf deity, and left, as one former friend put it, “a flaming asshole.” A trail of burnt friendships and stillborn business deals followed. “Coke killed everything good about the ’60s,” said Curtis Hesselgrave. “Egos got huge, money got big, and suddenly, instead of peace and love, it was rip-offs and paranoia and guns."

Hynson's one-time partner Johnny Gale turned from a colorful acid-dipped swashbuckler to a full-blown coke baron notorious for hosting depraved orgies at one of his Laguna Beach oceanfront villas. Gale met his end in 1980 after being decapitated in a high-speed crash, presumably chased by rival drug gangs. Gale was driving Hynson’s Mercedes, and his body was so mutilated that police listed Hynson himself as D.O.A. at the morgue until, three days later, Hynson arrived to claim the wreckage. “Maybe I should have stayed dead,” reflects Hynson.

Hynson eventually lost everything, including his marriage. His lingering connections with the now-defunct Brotherhood forced him to go into “alley mode,” as he calls it. Living as a homeless person, he found, was a convenient way to go into self-imposed exile while never leaving the country. Hynson bounced from couch to couch, garage to shaping bay. Picked up for vagrancy or minor drug possession, he would neglect his paperwork or probation requirements and end up in various county jails for six months at a time.

But through the next two decades, Hynson says, he always kept shaping, even mowing a blank in one customer’s living room because he lacked a shaping room or even a garage at the time. By the early '90s, however, the longboard revival spurred new interest in Hynson’s now-classic ’60s signature models. Board orders increased to a point where Hynson could rent a shaping booth and begin to slowly piece together a semblance of his former life.

A major turning point came in 1997 when, on a lark, he shaped a few downrail keel-fin fishes and set them for sale at the Surf Ride store, then managed by former pro and board aficionado Sean Mattison. At first, Mattison was leery of trying such an oddball design, but with a classic green-eggs-and-ham sales approach Hynson badgered him into taking it out at the Oceanside jetty for a trial surf. The result? A revelation. Mattison never had experienced such speed and drive, and at the end of the session he came in shaking his head. “I had this guy run down and go, ‘I don't know what you’re riding, but I want one just like it!’ And he hands me his business card,” he remembers.

Based on such positive feedback, Mattison commissioned a full line of Hynson Fishes, designating a section of the store as largely dedicated to the new boards. He helped Hynson set up a website and national dealer network. While the Red Fin replicas had enjoyed steady sales, Hynson was again looking for something that would hardwire the link between speed and maneuverability. Working once again with Curtis Hesselgrave, in 2004 they designed the Twinzer Quad Fish. Retro and futuristic at the same time, Twinzer sales have been brisk.

Hynson is part of a small, fast-shrinking group of over-60 shapers (Hynson shaped his first board in 1959) who bridge the eras from balsas to PU foam to epoxy. But where most of the legendary shapers have been crafting trophy longboards and wall-hangers for the gold-card demographic, Hynson never lost his passion for tinkering—or speed.

“His boards are relevant in 2007 because he listens and he applies,” says Mattison. “If Mike makes you a board, you're going to have a positive emotional experience. His lines and shapes are different than anybody else. There's an element of surprise and unknown, and that’s the coolest part. I’m tapping into that same stoke of discovery of when Mike was testing the downrailer at Maalaea and Pipe back in the ’70s.”

* * *

Back in the office, Hynson offers me a pour of sparkling grape juice. Following a near-fatal brush a few years ago with viral myocarditis, a heart-eating virus that left him gasping for breath in a San Diego free clinic, Hynson has been off all substances, including alcohol.

His health otherwise is good. He keeps busy pinballing from one project to the other, wearing his standard gear: a tool belt and a singlet tee sporting a silver namaste symbol. Stripped to the core, Hynson is first and foremost a craftsman. He is rarely comfortable without a hand tool—a roofing hammer, a hand plane, a socket wrench—within reach. His hands, rough and expressive, are used over a day’s labor to blend a tail section, frame up a greenhouse deck, wire a stereo, pet three feisty Chihuahuas, or mime a funny shaggy-dog tale about faking insanity to flunk his Selective Service exam.

His latest project, he tells me, is to rig a members-only webcam so that his clients can watch their boards being shaped. “I just have to be careful about where I scratch,” he chuckles.

Before I leave, I ask him about the wave back at Cape St Francis in 1963. Turns out that despite Bruce Brown’s hyperbole, it broke for only about 90 minutes, all up. The extreme tides killed it as quickly as they had created it that morning. Further, I’ve found since visiting South Africa a few years ago that the huge dunes that feed the flat sand bottom which in turn creates formed the perfect wave have been covered with golf grass and condos. Sand starvation has exposed the irregular rock reef, and although the swells arrive for a handful of days each year, the wave is now a parody of itself.

Hynson, playing jack of hearts over queen of spades, seems indifferent to the news. He’s never been back and seems content to hold the memory as is.

“You know, everything ends. No one’s gonna be the greatest forever. When you’re great, you’re great. But you have to realize that from that point on you’re gonna have to wait for when you’re not great, because that’s, like, right around the corner.

“You know what I mean?”

[Photos: Bruce Brown, Jeff Divine, Ron Stoner, Jim Driver]